I am completing a miniature book titled, “3000 Winawer Miniatures”. Below are some games from this book that will be out later this year.

The opening moves of the Winawer, just in case you didn’t know are: 1.e4 e6 2.d4 d5 3.Nc3 Bb4.

**************************

W. Muir-F. Stratholt, 1934

1.e4 e6 2.d4 d5 3.Nc3 Bb4 4.e5 c5 5.Bd2 cxd4 6.Nb5 Bc5 7.b4 Bf8 8.Qg4 g6 9.Nf3 Nc6 10.Bd3 a6 11.Nbxd4 Qc7 12.Nxc6 bxc6 13.O-O Ne7 14.Rfe1 Bg7 15.Bg5 O-O 16.Bf6 Nf5 17.Bxf5 exf5 18.Qh4 Re8 19.Ng5 h6 20.Nf3 Be6 21.Re3 Rac8 22.Rae1 Qa7 23.Nd4 c5 24.Rh3 h5 25.Qg5 1-0

Marriott-Arnold

corres., 1945

1.e4 e6 2.d4 d5 3.Nc3 Bb4 4.e5 c5 5.Bd2 cxd4 6.Nb5 Bc5 7.b4 Bb6 8.Qg4 g6 9.Nd6+ Kf8 10.Qf4 f6 11.exf6 Bc7

12.Qh6+! (12…Nxh6 13.Bxh6+ Kg8 14.f7#) 1-0

R. Steiner-V. Walsh

corres.

Australia, 1947

1.e4 Nc6 2.d4 d5 3.Nc3 e6 4.Nf3 Bb4 5.Bd3 Nf6 6.Bg5 b6 7.O-O Bxc3 8.bxc3 dxe4 9.Bxe4 Qd6 10.Bxc6+ Qxc6 11.Ne5 Qe4 12.f3 Qf5 13.Bc1 Nd5 14.Re1 Nxc3 15.Qd2 Nd5 16.c4 Ne7 17.Ba3 Bd7 18.Rad1 Rd8 19.Bxe7 Kxe7 20.d5 f6 21.d6+ cxd6 22.Qxd6+ Ke8 23.Nc6 Qc5+ 24.Qxc5 bxc5 25.Rxe6+ 1-0

Reinhard Fuchs-Weyerstrass

Soest, 1972

1.e4 e6 2.d4 d5 3.Nc3 Bb4 4.e5 c5 5.Be3 Nc6 6.f4 Qa5 7.Qd2 Nge7 8.Nf3 Nf5 9.Bf2 Bd7 10.Be2 Rc8 11.Kf1 cxd4 12.Nxd4 Ncxd4 13.Be1 Nxe2 14.Qxe2 d4 15.g4 dxc3 0-1

David Schurr-Robert Wilson

corres., 1951

1.e4 e6 2.d4 d5 3.Nc3 Bb4 4.e5 c5 5.a3 Bxc3+ 6.bxc3 Ne7 7.Nf3 Qa5 8.Qd2 Qa4 9.Rb1 c4 10.g4 Nbc6 11.h4 b6 12.Bh3 O-O 13.g5 Bd7 14.h5 g6 15.Bg4 Nf5 16.Nh2 Nce7 17.Bd1 Kh8 18.Ng4 Ng8 19.Nf6 ! +- Nxf6 20.gxf6 Be8 21.Qg5 Qa5 22.Rb4! (Eliminating all counter play.) 22…b5 23.Bg4 h6 24.Bxf5! (After 24…Bxf5 hxg5 25.hxg6+ Kg8 26.g7, White has a pretty pawn chain and mate coming.)

1-0

Schadler-Dors

corres.

Europe, 1989/90

1.e4 e6 2.d4 d5 3.Nc3 Bb4 4.exd5 Bxc3+ 5.bxc3 exd5 6.Bd3 Nf6 7.Ba3 Be6 8.Ne2 Nbd7 9.O-O Nf8 10.Ng3 Qd7 11.Rb1 c6 12.Qe2 Qc7 13.Nf5 O-O-O 14.Ba6 Bxf5 15.Bxb7+ Qxb7 16.Rxb7 Kxb7 17.Rb1+ 1-0

Brunner (2460)-Lempereur (2226)

Clichy Open

France, 1991

1.e4 e6 2.d4 d5 3.Nc3 Bb4 4.e5 c5 5.a3 Bxc3+ 6.bxc3 Ne7 7.Qg4 Kf8 8.a4 b6?! (This weakens the queenside, the same side that Black seeks counterplay in the French.) 9.Bb5 Qc7 10.Nf3 Ba6 11.O-O Bxb5 12.axb5 a5 13.dxc5 bxc5 14.c4 Nd7 15.cxd5 Nxd5 16.c4! +- (Solidifying White’s passed pawn.) 7…Ne7?! (Black had the better 7…Nb4 and 7…N5b6. The text leads to a cramp position.) 17.Qe4 Nb6 18.Rd1 Rc8 19.Rd6 h6 20.Bd2 g6 21.Bxa5! 1-0

R. Babich-H. Nordah

World Jr. Ch.

Bratislava, 1993

1.e4 e6 2.d4 d5 3.Nc3 Bb4 4.e5 c5 5.a3 Bxc3+ 6.bxc3 Qc7 7.Bd2 Ne7 8.Qg4 cxd4 9.cxd4 Qxc2 10.Qxg7 Rg8 11.Qf6 Nbc6 12.Nf3 Qe4+ 13.Be3 Rg6 14.Qh8+ Rg8 15.Qf6 Rg6 16.Qh8+ 1/2-1/2

Georges De Schryver-Hayden Lewin

corres.

Masters Tournament

IECC, 1997

1.e4 e6 2.d4 d5 3.Nc3 Bb4 4.e5 c5 5.Be3 c4 6.Qg4 g6 7.a3 Bxc3+ 8.bxc3 Qa5 9.Bd2 Nh6 10.Qf3 Nf5 11.g4 Nh4 12.Qf6 O-O 13.Bh6 Nf5 14.gxf5 Qxc3+ 15.Kd1 Qxd4+ 16.Ke2 Qg4+ 17.f3 gxf5 18.fxg4 1-0

Van Den Doel (2560)-Tondivar (2357)

Netherlands Women’s Ch., ½ Final

Leeuwarden, Mar. 16 2004

1.e4 e6 2.d4 d5 3.Nc3 Bb4 4.e5 c5 5.a3 Ba5 6.Bd2 Nc6 7.Qg4 Nge7 8.dxc5 O-O 9.f4 f6 10.Nf3 fxe5 11.fxe5 Ng6 12.O-O-O Ngxe5 13.Nxe5 Nxe5 14.Qg3 Nc6 15.Nb5 Bxd2+ 16.Rxd2 b6 17.Nc7 Rb8 18.Bb5 1-0

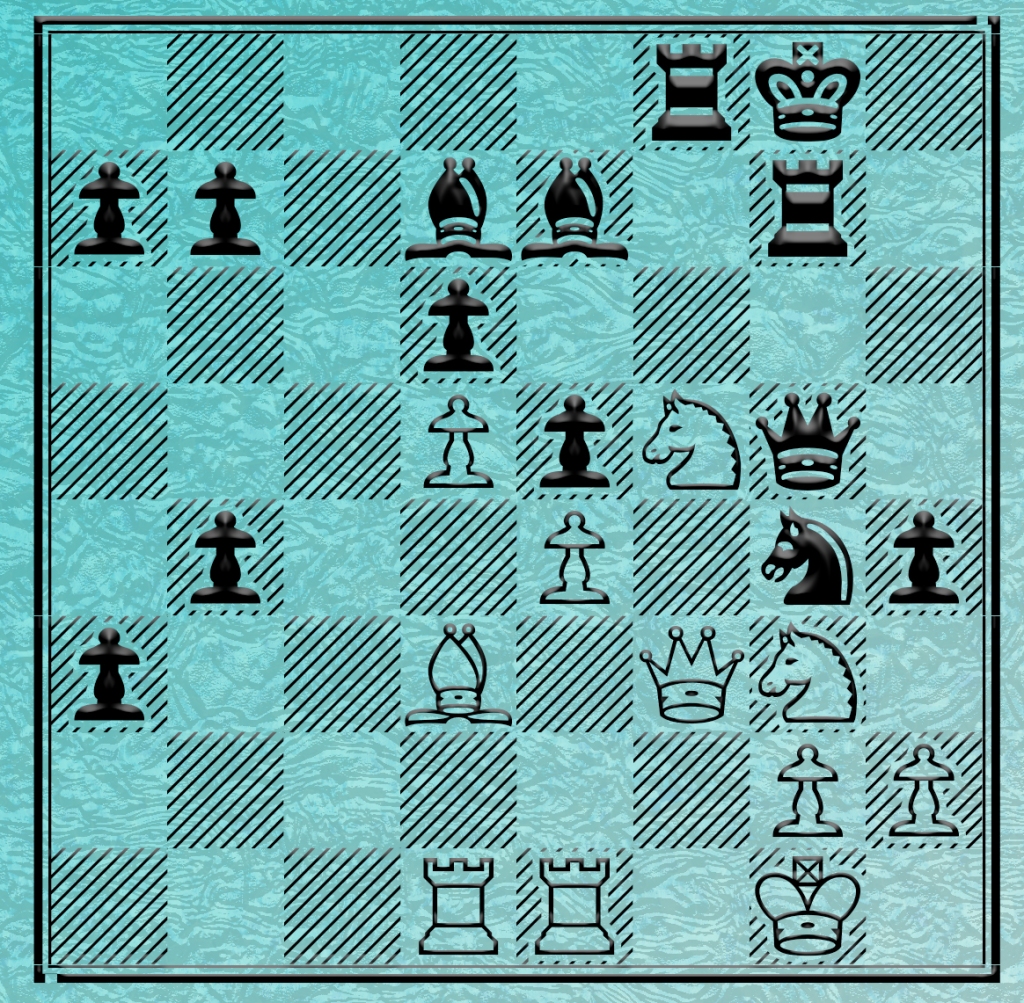

Wichert (2255)-Payce

corres.

Webchess Open

ICCF, 2006

1.e4 e6 2.d4 d5 3.Nc3 Bb4 4.e5 c5 5.a3 Ba5 6.Bd2 cxd4 7.Nb5 Bc7 8.f4 a6 9.Qg4 g6 10.Nxc7+ Qxc7 11.Bd3 Nc6 12.Nf3 Nge7 13.O-O Bd7 14.Qh4 O-O-O 15.b4 b5 16.a4 bxa4 17.Bxa6+ Kb8 18.Qf2 Na7 19.b5 Bxb5 20.Rfb1 Ka8 21.Bxb5 Nxb5 22.Rxb5 Qxc2 23.Nxd4 Qc7 24.Rxa4+ Qa5 25.Raxa5mate 1-0

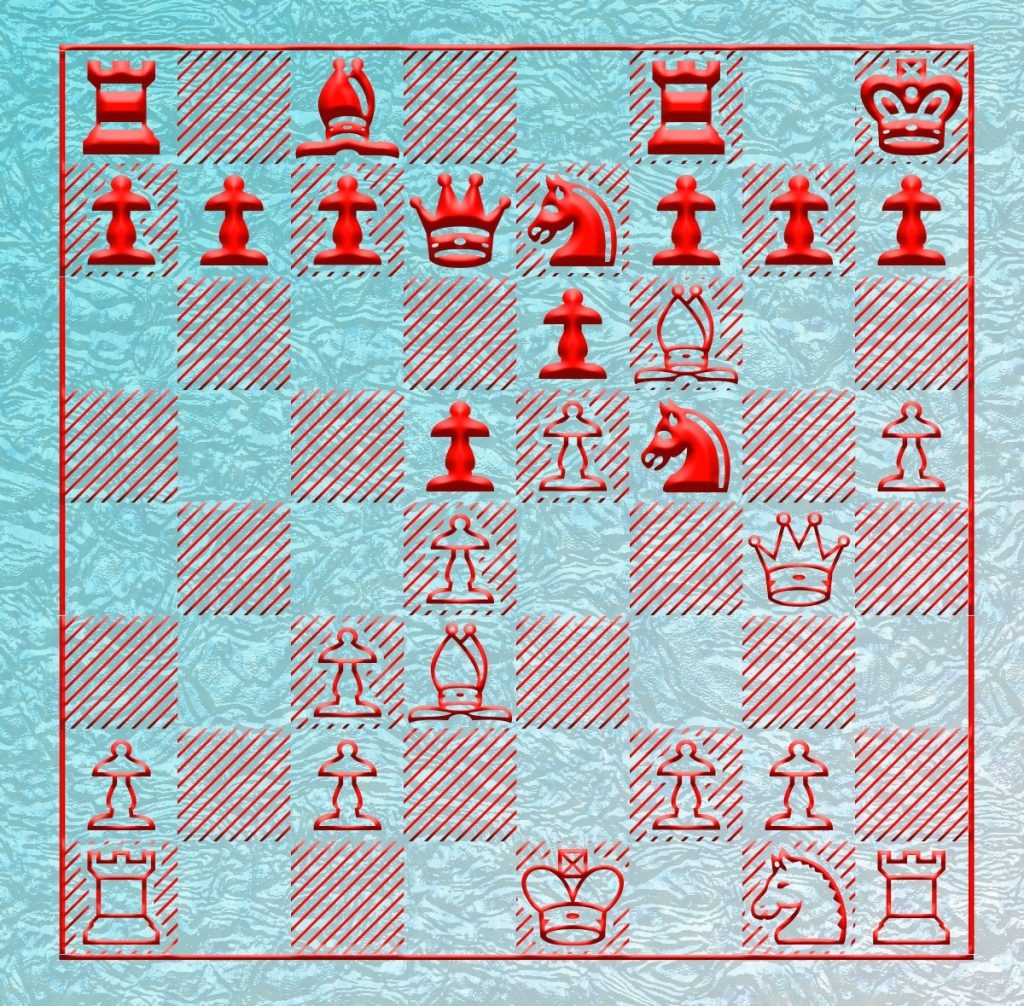

E. Blomqvist (2418)-E. Boric (2292)

Rilton Cup

Stockholm, Jan. 4 2009

1.e4 e6 2.d4 d5 3.Nc3 Nc6 4.Nf3 Bb4 5.e5 Qd7 6.Bd2 b6 7.Bb5 a6 8.Bd3 f5 9.exf6 Nxf6 10.O-O O-O 11.Re1 Bxc3 12.Bxc3 g6 13.Bd2 Qd6 14.Bh6 Re8 15.Qd2 Bb7 16.Ne5 Ne4 17.Bxe4 dxe4 18.Ng4 Red8 19.Bg5 Qxd4 20.Qf4 e3 21.Nh6+ (21…Kg7 22.Qf7+ Kh8 23.Bf6+ wins.) 1-0

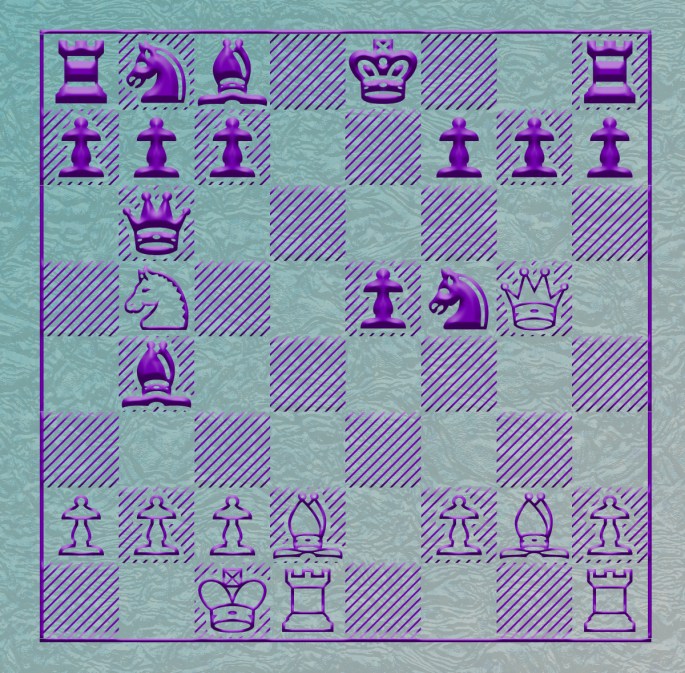

Escalante (2020)-“gxtmf1” (1551)

Thematic Tournament

http://www.chess.com, June/July 2009

1.e4 e6 2.d4 d5 3.Nc3 Bb4 4.e5 c5 5.Bd2 cxd4 6.Nb5 Be7 7.Qg4 Kf8 8.Nf3 Qb6 9.Bd3 h5 10.Qf4 Nc6 11.Nbxd4 Nxd4 12.Nxd4 g5 13.Qe3 Qxb2?! 14.O-O Bc5?? 15.Nxe6+! +- Bxe6 16.Qxc5+ Kg7 17.Rfb1 b6 18.Qe3 Qa3 19.Qxg5+ 1-0

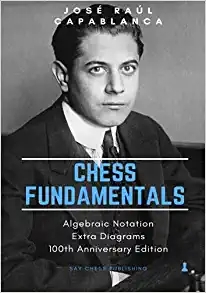

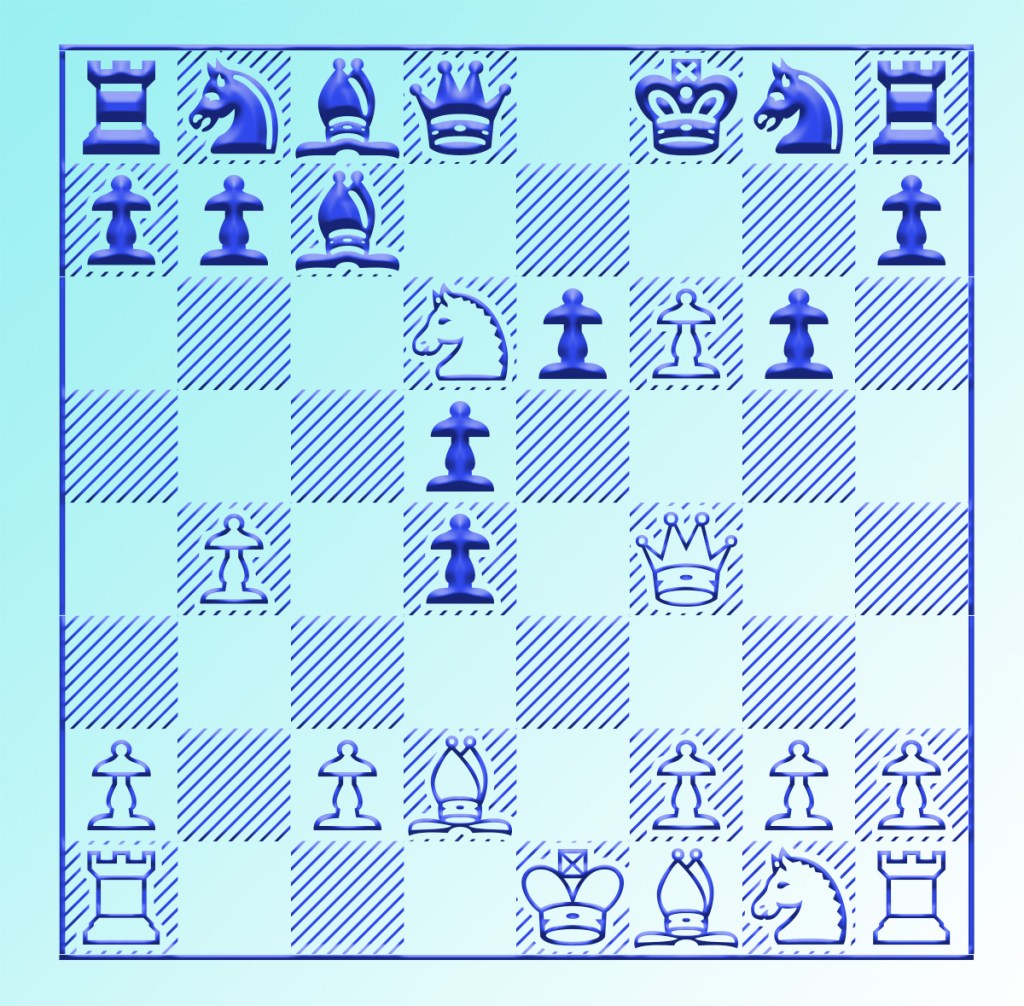

“Mikevic34”-Escalante

Cell Phone Game, Mar. 2016

1.e4 e6 2.d4 d5 3.Nc3 Bb4 4.e5 c5 5.Qg4 g6!? (This move is not as well known as 5…Kf8 or 5…Ne7. But it provides for some fast, sharp play.) 6.Bg5?! Qa5! 7.Nge2?! (Already White seems to be having problems with his king still stuck on e1.) 7…Nc6 8.g3 cxd4 9.Nxd4 Bxc3+ 10.bxc3 Qxc3+ 11.Bd2 Qxa1+ 12.Qd1 Qxd4 (Also winning, but considerably weaker, is 12…Nxd4 13.Qxa1 Nxc2+ -+) 13.Bd3 Qxe5+ 14.Be3 d4 15.Bb5? Qxb5 0-1

I have been writing this blog, weekly, since 2018. I have had great fun writing here, and it has (hopefully) made me a better player. I appreciate all those who have responded to this blog with questions comments, and occasionally games. And I hope to have made a positive influence on your play and appreciation of chess.

But my interest has been shifting and I do want to complete some book ideas and so I need to back away from this blog.

If you have a game you want to share, or show off to the world, now is your chance! Send a copy of your game (in PGN, text, DN or AN), and I will annotate it. Free!

Or if you have a question or an area you want covered, again, email me! Love to hear from you!

Enjoy the game and the day. May both be bright for you!