Recently I was going over an old collection of some 1990s games.

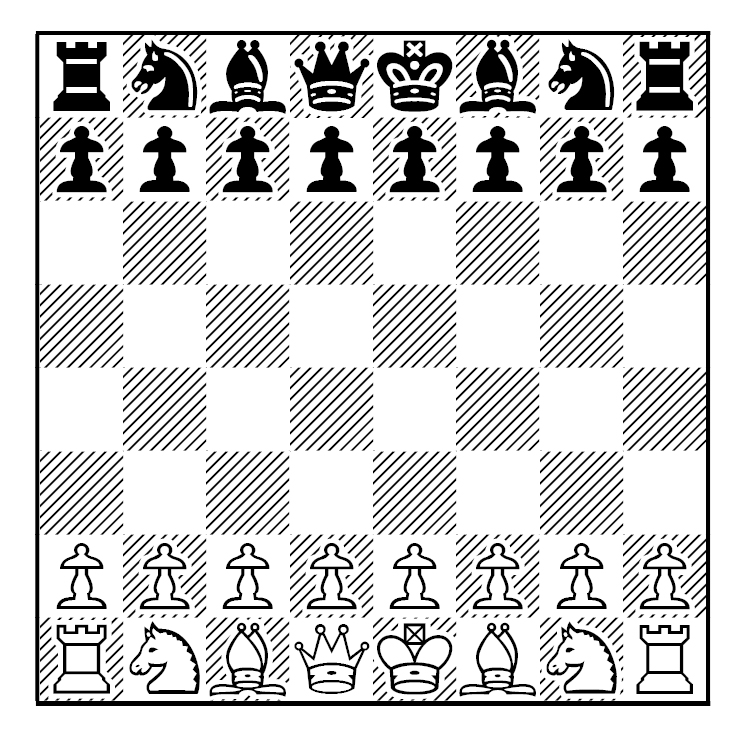

I found this little-known gambit in the French. The opening moves were 1.e4 e6 2.d4 d5 3.Nc3 dxe4, and now instead of 4.Nxe4 (the Rubinstein), White plays 4.f3. This tempts Black to play 4…exf3 5.Nxf3, and White has an extra developing move for the pawn.

I could not find a name for this gambit. So, I made one up. And in keeping with convention of naming openings that feature an early f3 and allowing Black to take the pawn apparently for free, I decided to name it, “The French Fantasy Variation”. Or FFV for short.

The first two games presented are the first two I found with these opening moves.

Beesley-Lynn

Auckland Open, 1999

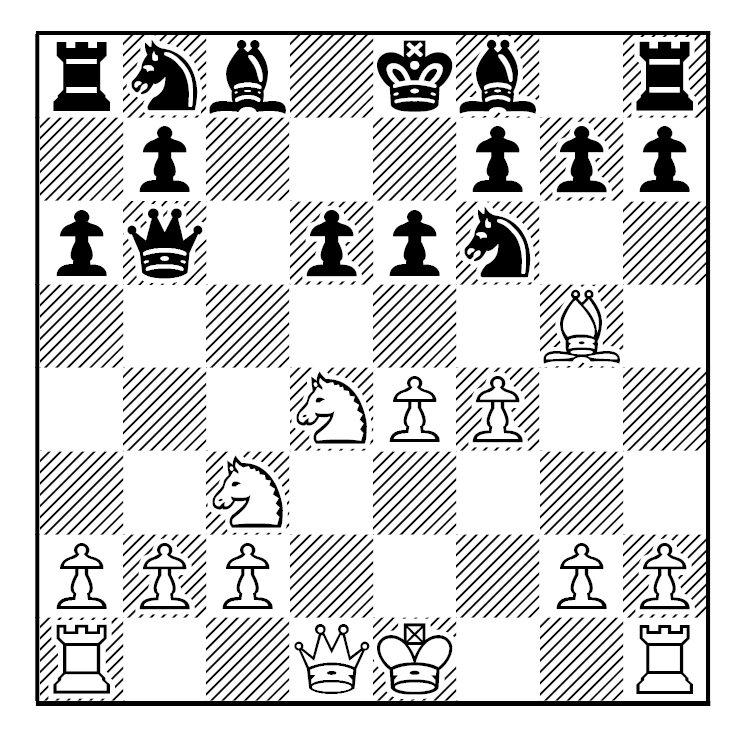

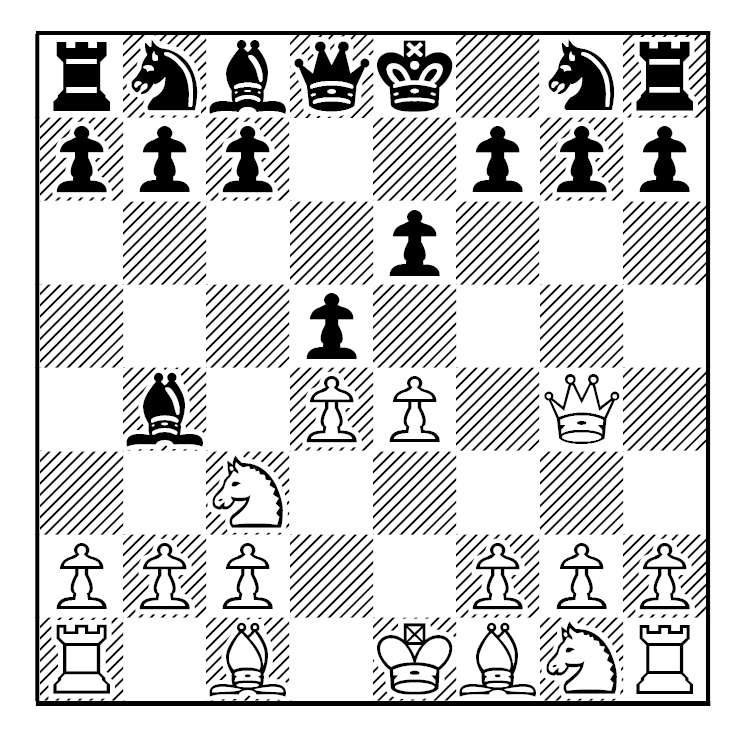

1.e4 c6 2.d4 d5 3.Nc3 dxe4 4.f3 exf3 5.Nxf3 Bg4 6.Be3 Nf6 7.h3 Bxf3 8.Qxf3 e6 9.Bd3 Bb4 10.O-O Bxc3 11.bxc3 Qd5 12.Qg3 Nbd7 13.c4 Qa5 14.Qxg7 Rg8 15.Qh6 Ke7 16.c5 Qc3 17.Rab1 b5 18.Rb3 Qa5 19.Bg5 Rxg5 20.Qxg5 Rg8 21.Qf4 Kd8 22.Qh4 Qd2 23.Qf2 Qg5 24.Ra3 Nd5 25.Rxa7 Rg7 26.Be4 N7f6 27.Bxd5 Nxd5 28.Rxf7 Rg6 29.Rf3 b4 30.Kh2 h5 31.Rg3 Qxg3+ 32.Qxg3 Rxg3 33.Kxg3 Ne3 34.Re1 h4+ 35.Kf2 Nxc2 36.Rxe6 Kc7 37.Re4 Na3 38.Rxh4 Nb5 39.d5 cxd5 40.Rxb4 Nc3 41.Ke3 Nxa2 42.Rb6 Nc3 43.Rd6 1-0

Stracy-Gibson

Auckland Open, 1999

1.e4 c6 2.d4 d5 3.Nc3 dxe4 4.f3 exf3 5.Nxf3 Bg4 6.Be3 Nf6 7.h3 Bxf3 8.Qxf3 e6 9.Bd3 Bb4 10.O-O Bxc3 11.bxc3 Qd5 12.Qg3 Nbd7 13.c4 Qa5 14.Qxg7 Rg8 15.Qh6 Ke7 16.c5 Qc3 17.Rab1 b5 18.Rb3 Qa5 19.Bg5 Rxg5 20.Qxg5 Rg8 21.Qf4 Kd8 22.Qh4 Qd2 23.Qf2 Qg5 24.Ra3 Nd5 25.Rxa7 Rg7 26.Be4 N7f6 27.Bxd5 Nxd5 28.Rxf7 Rg6 29.Rf3 b4 30.Kh2 h5 31.Rg3 Qxg3+ 32.Qxg3 Rxg3 33.Kxg3 Ne3 34.Re1 h4+ 35.Kf2 Nxc2 36.Rxe6 Kc7 37.Re4 Na3 38.Rxh4 Nb5 39.d5 cxd5 40.Rxb4 Nc3 41.Ke3 Nxa2 42.Rb6 Nc3 43.Rd6 1-0

These games show some promise for the FFV! I am excited so far! Do these New Zealanders know something about chess opening that most other players don’t? I had to look up some more games, just to make sure that this opening, while definitely exciting, is also somewhat sound. I don’t want any negative surprises hitting me while playing this in an OTB or online tournament.

During my quest I found that Black can also do well. More troubling is that I didn’t find too many Master level games with this opening. Now it could be that 4.f3 was hardly played as there was very little theory on it, or the Master lever players didn’t think it was a great, or even a good, gambit to play. Of course, one way of deciding is to analyze it for oneself, namely me!

Let’s look at several games in which Black did well.

Sebastian Gramlich (2080)-Holger Rasch (2259)

Rhein Main Open

Bad Homburg, Germany, June 10 2004

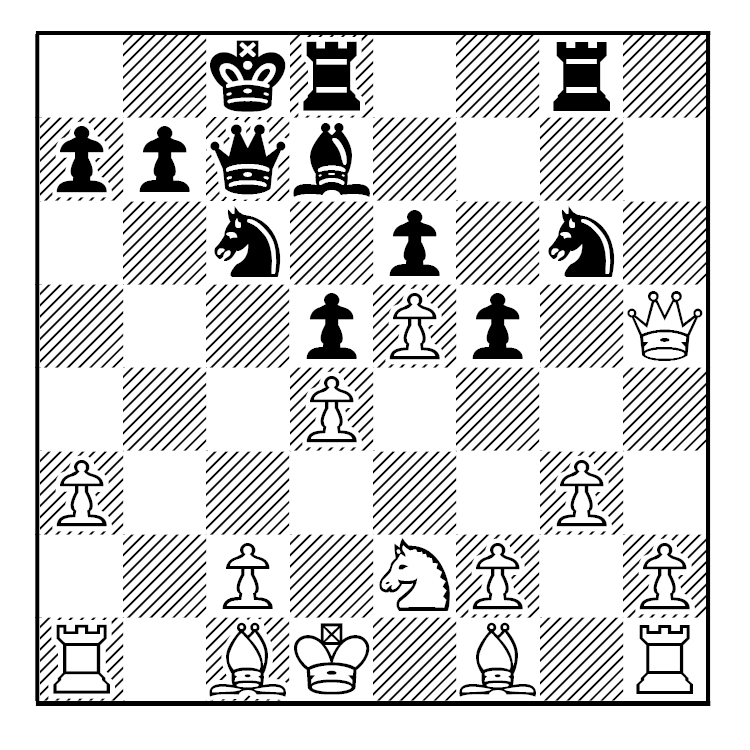

1.d4 d5 2.e4 e6 3.Nc3 dxe4 4.f3 exf3 5.Nxf3 Nf6 6.Bd3 c5 7.O-O cxd4 8.Ne4 Nc6 9.Nfg5 Be7 10.Bd2 h6 11.Nxf7 Kxf7 12.Qh5+ Kg8 13.Nxf6+ Bxf6 14.Rxf6 gxf6 15.Qg6+ Kf8 16.Rf1 f5 17.Bxf5 Ke7 18.Re1 Qg8 19.Qh5 Bd7 20.Qh4+ Kd6 21.Bf4+ Kc5 22.Bd3 a6 23.Bc7 Qg5 24.b4+ Kxb4 25.c3+ Kxc3 26.Qh3 Kb4 27.Bb6 Qd2 28.Rb1+ Ka3 29.Bc4+ Qe3+ 30.Qxe3+ dxe3 31.Bc5+ Ka4 32.Rb3 Nb4 33.Rxb4+ Ka5 34.a3 b5 35.Bxe3 Rac8 36.Be2 Bc6 37.g3 Bd5 38.Bd2 Kb6 39.a4 Rc2 40.Rd4 Kc5 0-1

Frits Bakkes-P. Borman (2214)

Nova Open

Haarlem, Netherlands, July 2 2004

1.d4 d5 2.e4 e6 3.Nc3 dxe4 4.f3 exf3 5.Nxf3 Nf6 6.Bc4 Be7 7.Bf4 O-O 8.Ne5 Nbd7 9.Qf3 Nb6 10.Bd3 Nbd5 11.Nxd5 Qxd5 12.Qg3 b6 13.O-O-O Qxa2 14.Nc6 Bd6 15.Bxd6 cxd6 16.Qxd6 Bb7 17.Nb4 Qa1+ 18.Kd2 Qa5 19.c3 Qg5+ 20.Kc2 Qxg2+ 21.Kb3 Rfd8 22.Qf4 Qg4 23.Qxg4 Nxg4 24.Rhg1 Nxh2 25.d5 Nf3 26.Rg3 Ne5 27.dxe6 fxe6 28.Rdg1 g6 29.Be2 a5 30.Nc2 a4+ 31.Ka3 Bd5 32.Re3 Nc4+ 33.Bxc4 Bxc4 34.Nd4 Rd6 35.Rge1 Kg7 36.Kb4 b5 37.Re5 h5 38.Rg1 Kh7 39.Reg5 Bd3 40.Nxb5 Bxb5 41.Kxb5 Rd5+ 42.Rxd5 exd5 43.Rd1 Rb8+ 44.Ka5 Rxb2 45.Rxd5 Kh6 46.c4 h4 47.c5 g5 48.c6 Rc2 49.Kb5 Rb2+ 50.Kc5 Kh5 51.Kd6 Rb6 52.Rc5 h3 53.Kc7 Rxc6+ 54.Kxc6 Kh4 55.Kd5 h2 56.Ke5 h1=Q 0-1

In the first two games Black played 5…Bg4 and lost both. In the second set of two, Black played 5…Nf6, and won both.

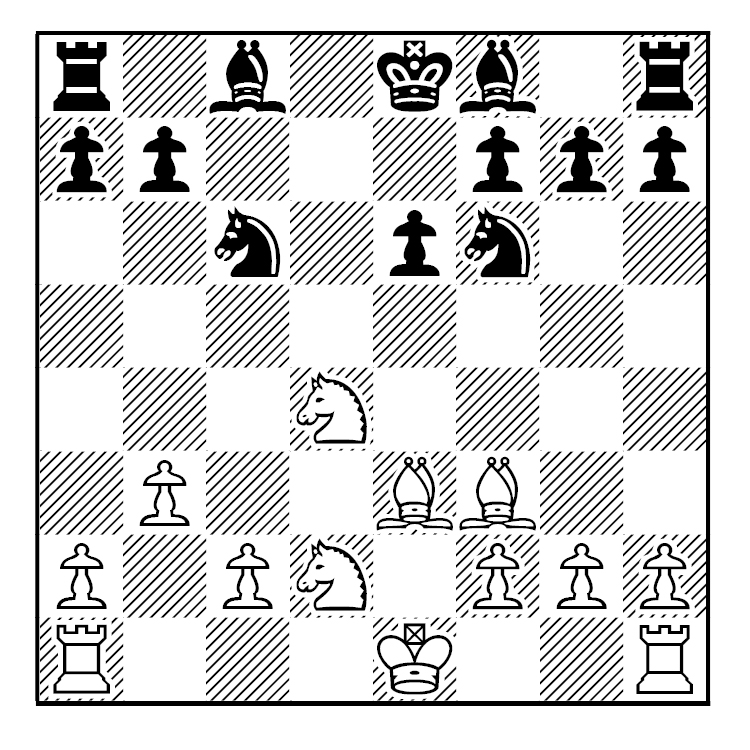

Does this mean Black’s 5th move determine the outcome of the game? Probably not. But such a decision is rendered academic as Black has a much better 4th move, namely 4.Bb4.

This move develops a piece, pins a knight, bring Black one move closer to castling, and still leaves White with a weakened kingside pawn structure.

And White must be careful. 5.fxe4? can lead to an immediate disaster.

Irfan Redzepovic (2115)-Hartmut Riedel (2230)

Landesliga N Bayern 95/96

Germany, 1996

1.e4 e6 2.d4 d5 3.Nc3 dxe4 4.f3 Bb4 5.fxe4? Qh4+ 6.g3 Qxe4+ 7.Kf2 Bxc3 8.bxc3 Qxh1 9.Nf3 Bd7 10.Ba3 Nf6 11.Qd3 Ng4+ 12.Ke2 Nxh2 0-1

And even with best moves, White should still lose.

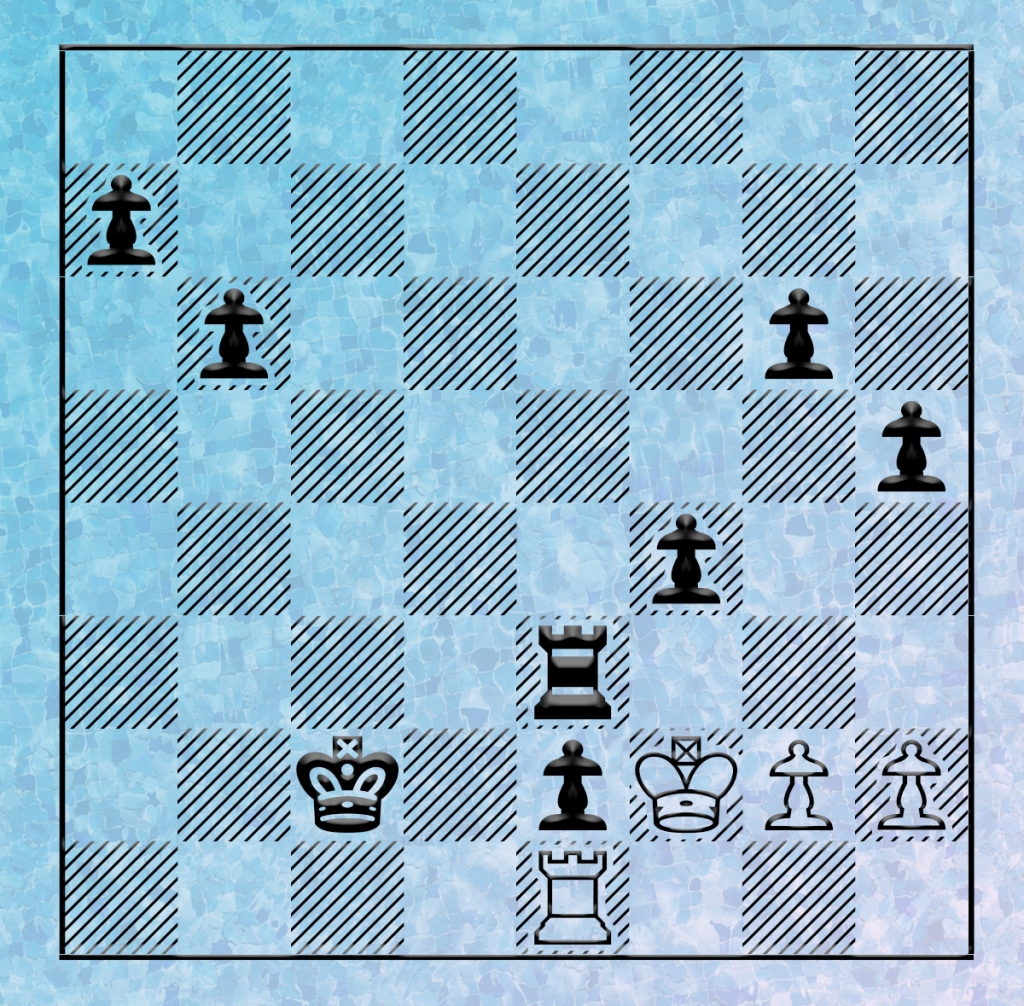

Jan Hennig-Gerhard Zach

Stuttgart Ch. B

Germany, 2004

1.d4 d5 2.e4 e6 3.Nc3 Bb4 4.f3 dxe4 5.fxe4 Qh4+ 6.g3 Qxe4+ 7.Qe2 Qxh1 8.Nf3 Bxc3+?! (Black can increase his pressure on White’s exposed King and unorganized pieces with 8…b6! If 9.Qb5+, then 9…c6 10.Qxb4 Qxf3.) 9.bxc3 Nf6 10.Ba3 (White wants to castle queenside and then play Bg2, trapping the black queen.) 10…b6 11.O-O-O Bb7 (Ba6!) 12.Bg2 Bxf3? (Ba6! would still do the trick!) 13.Bxf3 Qxd1+ 14.Qxd1 +- c6 15.Qh1 Kd7 16.c4 Rc8 17.g4 h6 18.h4 g5 19.hxg5 hxg5 20.Qh6 Ne8 21.Qf8 Kc7 22.Qxf7+ Nd7 23.Qxe6 Ng7 24.Qxc6+ Kd8 25.Qd6 Ne8 26.Qe7+ Kc7 27.d5 1-0

White of course, does not have to play 5…fxe4. But other moves result in other problems for White.

Hagen Oettinger (2151)-Filip Daniel Goldstern (2391)

Seefeld Open

Austria, Sept. 12 1999

1.d4 e6 2.e4 d5 3.Nc3 dxe4 4.f3 Bb4 5.Be3 Nf6 6.a3 Nd5 7.Qd2 Bxc3 8.bxc3 exf3 9.Nxf3 c6 10.c4 Nxe3 11.Qxe3 Qa5+ 12.Nd2 Nd7 13.Bd3 c5 14.d5 Qc3 15.Rd1 Qe5 16.Qxe5 Nxe5 17.Ne4 b6 18.O-O Ke7 19.Ng5 f6 20.Be4 Rb8 21.Nf3 Nxc4 22.Rfe1 e5 23.Nh4 Nd6 24.a4 Bd7 25.Ra1 c4 26.g3 Rbc8 27.c3 Rc5 28.Ng2 f5 29.Bf3 Kf6 0-1

Tim McGrew (1221)-Ron Gore (1598)

Michigan Amateur Open

Kalamazoo, Oct. 23 2004

1.d4 d5 2.e4 e6 3.Nc3 dxe4 4.f3 Bb4 5.a3 Bxc3+ 6.bxc3 Nf6 7.Bg5?! h6 8.Bxf6 Qxf6 9.fxe4 Qh4+ 10.Kd2 Qxe4 11.Nf3 O-O 12.Bd3 Qf4+ 13.Ke2 Nc6 14.Rf1 Qd6 15.Kf2 b6 16.Kg1 Bb7 17.Qe1 Ne7 18.Qe3 Bxf3 19.Rxf3 Nd5 20.Qd2 Rad8 21.Rg3 Qf4 22.Qe1 c5 23.Rf3 Qc7 24.Qe4 g6 25.Qe1 cxd4 26.cxd4 Ne7 27.Qh4 Qc3 28.Raf1 Qxd4+ 29.Qf2 Qxf2+ 30.R3xf2 Kg7 31.Rf4 Nf5 32.R1f3 Rd4 33.Rxd4 Nxd4 34.Rf4 e5 35.Re4 f6 36.Kf2 Rc8 37.Rg4 f5 38.Rg3 e4 39.Be2 Nxe2 40.Kxe2 Rxc2+ 41.Kd1 Rc5 42.Re3 Kf6 43.Kd2 Ke5 44.Rh3 h5 45.Rg3 Rc6 46.Rb3 f4 47.Rb5+ Rc5 48.Rb3 Kd4 49.Rb4+ Rc4 50.Rb1 e3+ 51.Ke2 Rc2+ 52.Kf1 e2+ 53.Ke1 Kd3 54.Rb3+ Rc3 55.Rb1 Rxa3 56.Kf2 Kc2 57.Re1 Re3 58.g3 g5

0-1

Dominic Klingher (1829)-George Stoleriu (2227)

European Youth Ch., Boys U14

Porec, Croatia, Sept. 21 2015

1.e4 e6 2.d4 d5 3.Nc3 dxe4 4.f3 Bb4 5.Be3 Nf6 6.a3 Bxc3+ 7.bxc3 Nd5 8.Qd2 b6 9.Bg5 f6 10.fxe4 fxg5 11.exd5 exd5 12.Nf3 g4 13.Ne5 O-O 14.c4 Ba6 15.cxd5 Qxd5 16.Nxg4 Qe4+ 17.Ne3 Re8 18.Bxa6 Nxa6 19.Kf2 Rad8 20.c3 Nc5 21.Rad1 Qf4+ 22.Ke2 Qg4+ 23.Kf1 Rxe3 0-1

Now I probably would not play this gambit in an OTB or online tournament. But speed chess, well, that’s another story!