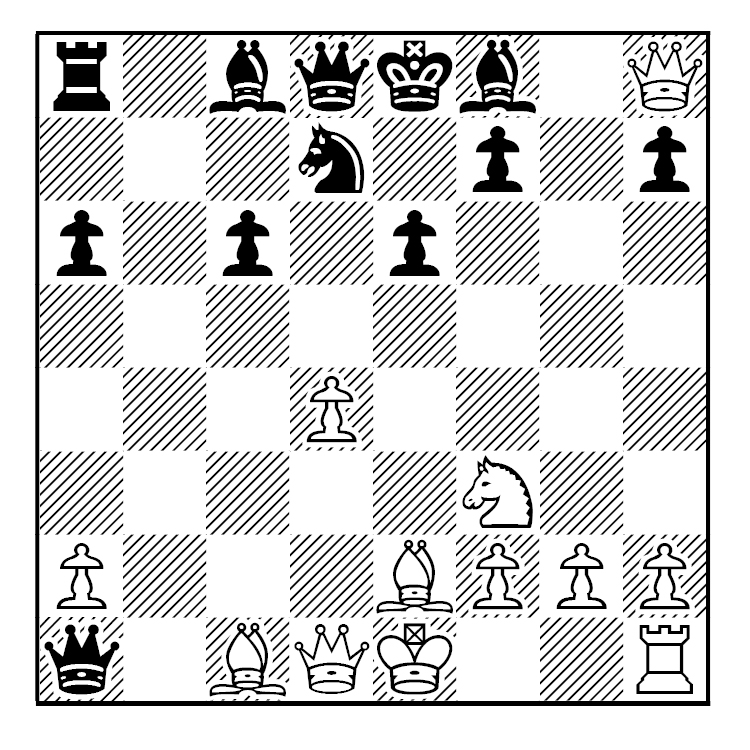

Many players dream of playing with four queens on the board. They admire the complications and the overall tactical possibilities.

Most of the know that endgames produce the most four-queen games. And yet, it is still not that common and the tactically-gifted usually don’t have their dreams transformed into reality.

But is there an opening that will let the players have the four queens.

The opening is from a Semi-Slav and the Encyclopedia of Chess Openings (ECO) classifies it as D47.

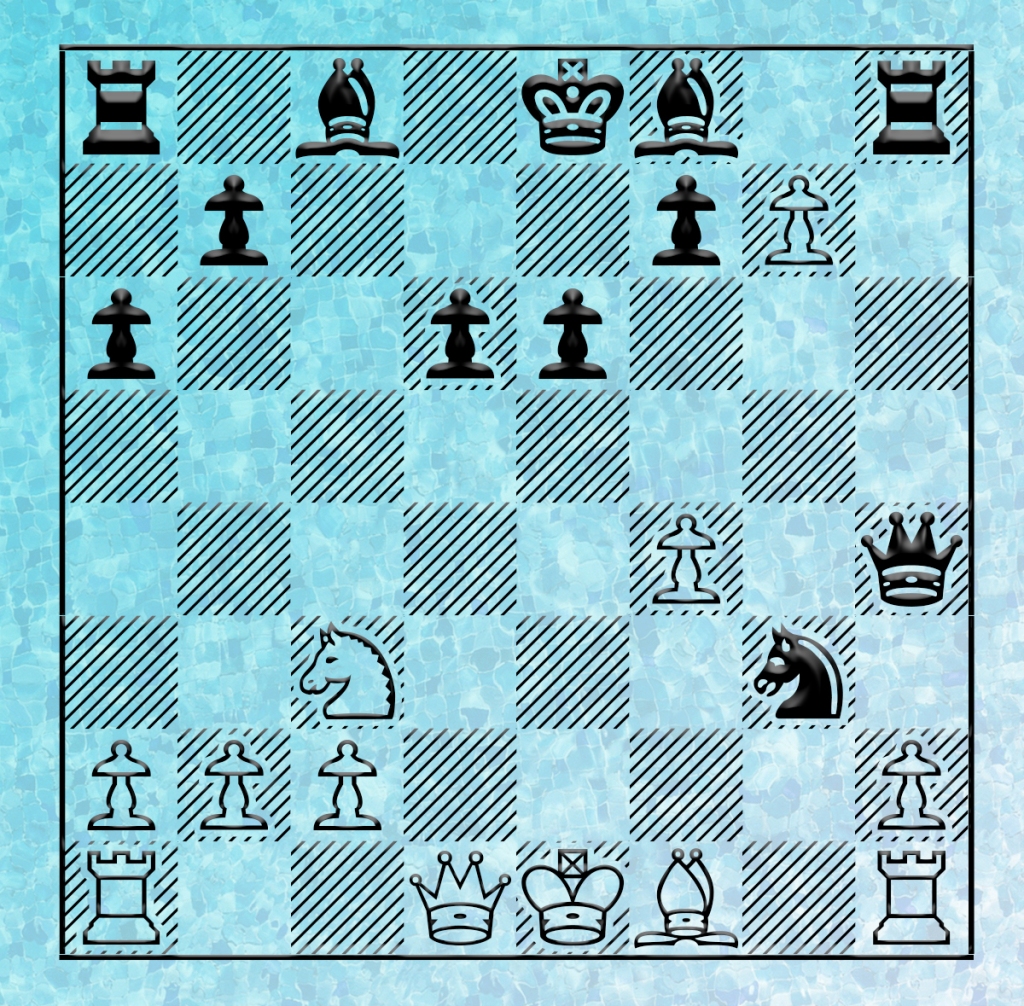

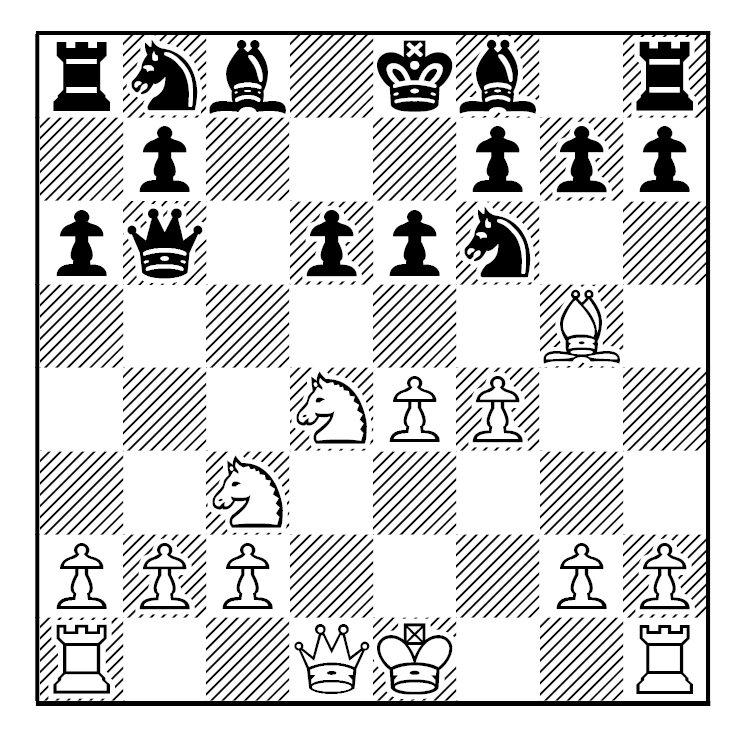

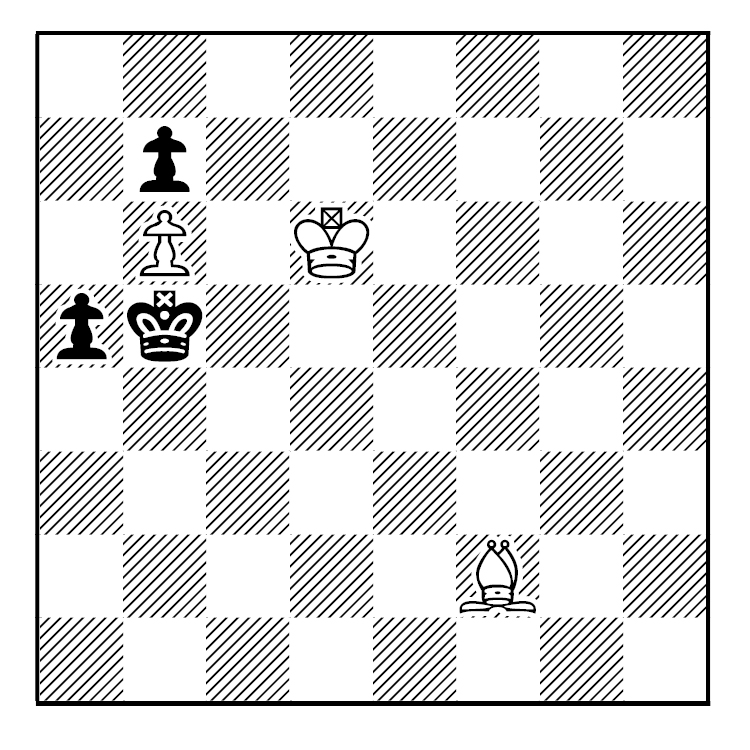

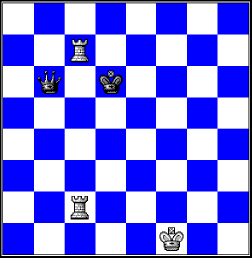

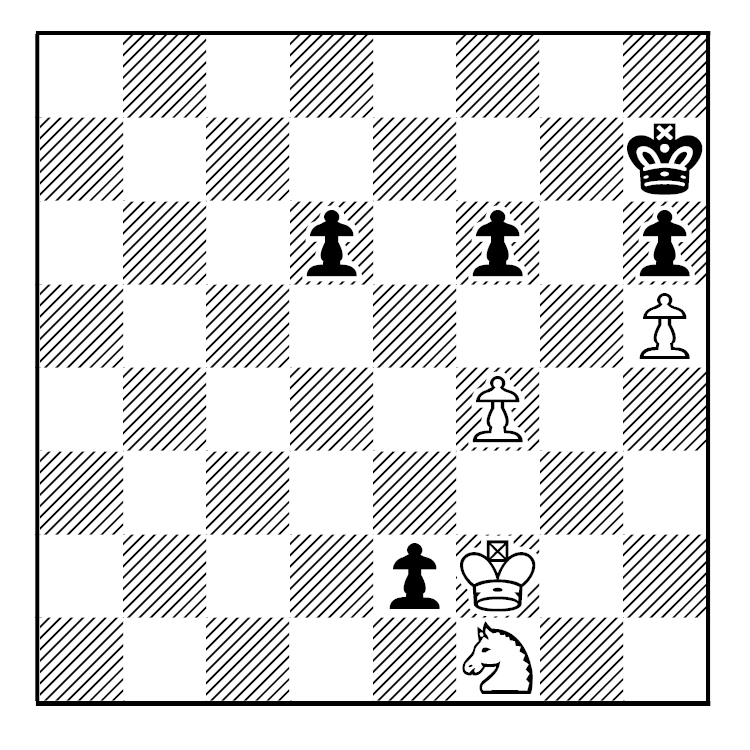

The opening moves to this multi-queen game are 1.d4 d5 2.c4 e6 3.Nc3 Nf6 4.Nf3 c6 (In case you are interested, these moves define the Semi-Slav), 5.e3 Nbd7 6.Bd3 dxc4 7.Bxc4 b5. Now White’s bishop is under attack, so he moves to e2. Now after 8.Be2 a6 9.e4 b4 10.e5! bxc3 11.exf6 cxb2 12.fxg7 bxa1=Q 13.gxh8=Q, we have four queens, with two of them on their original squares and the other two are far off on corner squares.

Here are all the moves and a diagram to help you.

1.d4 d5 2.c4 e6 3.Nc3 Nf6 4.Nf3 c6 5.e3 Nbd7 6.Bd3 dxc4 7.Bxc4 b5 8.Be2 a6 9.e4 b4 10.e5! bxc3 11.exf6 cxb2 12.fxg7 bxa1=Q 13.gxh8=Q.

Now let’s get to some games and analysis.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Black best response, after 13.gxh8=Q is to activate his second queen with 13…Qa5+. Anything else puts his game into jeopardy.

J. Kjeldsen-T. Christensen

Arhus, 1995

1.d4 d5 2.c4 e6 3.Nc3 Nf6 4.Nf3 c6 5.e3 Nbd7 6.Bd3 dxc4 7.Bxc4 b5 8.Be2 a6 9.e4 b4 10.e5 bxc3 11.exf6 cxb2 12.fxg7 bxa1=Q 13.gxh8=Q c5?! 14.O-O Bb7 15.Qxh7 Qxa2 16.Ng5 Qf6 17.Nxf7 Qg7 18.Qxg7 1-0

CM Asmund Hammerstad (2205)-Pavol Sedlacek (2233)

European Club Cup

Rogaska Slatina, Slovenia, Sept. 28 2011

1.d4 Nf6 2.Nf3 d5 3.c4 c6 4.Nc3 e6 5.e3 Nbd7 6.Bd3 dxc4 7.Bxc4 b5 8.Be2 a6 9.e4 b4 10.e5 bxc3 11.exf6 cxb2 12.fxg7 bxa1=Q 13.gxh8=Q Qxa2 (A little more active than 13…c5, but not by much.) 14.O-O Qf6 15.Qxh7 Qg7 16.Qhc2 Qd5 17.Ng5 Bb7 18.Bf3 Qb5 19.Bh5 O-O-O 20.Be2 Qa5 21.Bd2 Qa3 22.Bf3 Nb8 23.Be3 Be7 24.Ne4 f5 25.Nd2 Qb4 26.Qe2 Qb5 27.Nc4 a5 28.Rb1 Bb4 29.Nd6+ Rxd6 30.Qxb5 Qd7 31.Qe5 Qe8 32.Rxb4 1-0

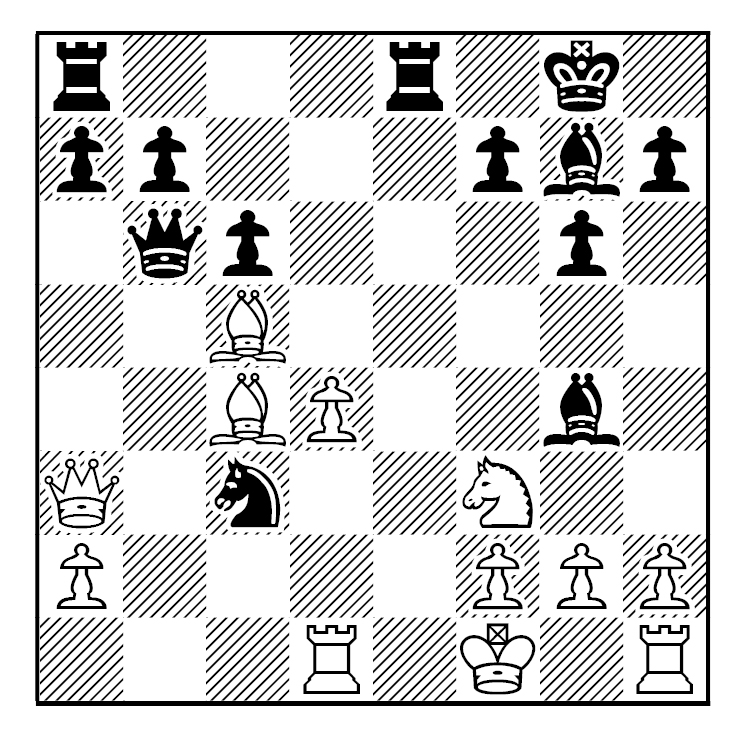

After Black’s 13…Qa5+, White must block the check and he has two main ways to do so. One is 14.Bd2, the other 14.Nd2. The move 14.Bd2 would seem to be the best, but only superficially. 14.Nd2 allows for more freedom for White’s pieces. That’s why White wants to enter these complications – to use his tactical abilities.

Here are a few games with 14.Bd2.

Benko-Pytel

Hastings, 1973

[ECO]

1.d4 d5 2.c4 e6 3.Nc3 Nf6 4.Nf3 c6 5.e3 Nbd7 6.Bd3 dxc4 7.Bxc4 b5 8.Be2 a6 9.e4 b4 10.e5 bxc3 11.exf6 cxb2 12.fxg7 bxa1=Q? 13.gxh8=Q Qa5+ 14.Bd2 Qxd1+ 15.Bxd1 Qf5 (15…Qb5 16.Qxh7 +/-) 16.O-O Bb7 17.d5 Qxd5 18.Qxh7 c5 19.Ba4 O-O-O 20.Bg5 Ne5 21.Ne1 c4 22.Bxd8 Qxd8 23.Qh8 f6 24.Qg8 Qd6 25.Nc2 Kc7 26.Ne3 Be7 27.Rd1 Qb6 28.Qe8 Bc5 29.Qd8mate 1-0

Lauber (2380)-Mosquera

World U20 Ch.

Medellin, 1996

1.d4 d5 2.c4 e6 3.Nc3 Nf6 4.Nf3 c6 5.e3 Nbd7 6.Bd3 dxc4 7.Bxc4 b5 8.Be2 a6 9.e4 b4 10.e5 bxc3 11.exf6 cxb2 12.fxg7 bxa1=Q 13.gxh8=Q Qa5+ 14.Bd2 Qxd1+ 15.Bxd1 Qxa2 16.O-O c5 17.dxc5 Bb7 18.Bg5 h6 19.Bxh6 O-O-O 20.c6 Bxc6 21.Bxf8 Qa5 22.Be2 Rxf8 23.Qb2 Bb5 24.Rc1+ Kd8 25.Ne5 Nxe5 26.Qxe5 Qb4 27.Qc7+ Ke8 28.Qb7 Qd6 29.Rc8+ Qd8 30.Rxd8+ Kxd8 31.Bxb5 axb5 32.Qxb5 1-0

Fletcher Baragar (2305)-Daniel Fernandez (2057)

Financial Concept Open

North Bay, Canada, Aug. 7 1999

1.d4 d5 2.c4 e6 3.Nc3 Nf6 4.Nf3 c6 5.e3 Nbd7 6.Bd3 dxc4 7.Bxc4 b5 8.Be2 a6 9.e4 b4 10.e5 bxc3 11.exf6 cxb2 12.fxg7 bxa1=Q 13.gxh8=Q Qa5+ 14.Bd2 Q5xa2 15.O-O Qxd1 16.Rxd1 h6 17.Ne5 Nxe5 18.dxe5 Bd7 19.Qf6 Be7 20.Qh8+ Bf8 21.Qf6 Be7 22.Qxh6 O-O-O 23.Qe3 c5 24.Qf3 Kb8 25.Be3 Bb5 26.Rxd8+ Bxd8 27.Bxb5 axb5 28.g3 b4 29.Qc6 b3 30.Bxc5 b2 31.Bd6+ Ka7 32.Bc5+ Kb8 1/2-1/2

Kamil Klim (2108)-Krzysztof Bulski (2396)

Lasker Memorial

Barlinek, June 2 2007

1.d4 d5 2.c4 c6 3.Nf3 Nf6 4.Nc3 e6 5.e3 Nbd7 6.Bd3 dxc4 7.Bxc4 b5 8.Be2 a6 9.e4 b4 10.e5 bxc3 11.exf6 cxb2 12.fxg7 bxa1=Q 13.gxh8=Q Qa5+ 14.Bd2 Qxd1+ 15.Bxd1 Qf5 16.O-O Bb7 17.d5 Qxd5 18.Qxh7 c5 19.Ba5 Bc6 20.Nh4 Qe4 21.Qxe4 Bxe4 22.Re1 Bd3 23.Nf3 Bg7 24.Ng5 Bf6 25.Ne4 Bd4 26.Bc7 Nf6 27.Ba4+ Bb5 28.Bc2 Kd7 29.Bb6 Nxe4 30.Bxe4 Bc6 31.Rd1 Bd5 32.Bc2 Rb8 33.Ba4+ Kd6 34.Ba5 Rb2 35.Rd2 Rb1+ 36.Rd1 Bxa2 37.h4 Rxd1+ 38.Bxd1 c4 0-1

Now for the stronger, and more fluid, 14.Nd2.

Krogius-Kamyshov

USSR, 1949

[ECO]

1.d4 d5 2.c4 e6 3.Nc3 Nf6 4.Nf3 c6 5.e3 Nbd7 6.Bd3 dxc4 7.Bxc4 b5 8.Be2 a6 9.e4 b4 10.e5 bxc3 11.exf6 cxb2 12.fxg7 bxa1=Q? 13.gxh8=Q Qa5+ 14.Nd2 Qf5 15.O-O Bb7 16.Qb3 Nc5 17.Ba3 Nxb3 18.Qxf8+ Kd7 19.Qe7+ Kc8 20.Nxb3 +- Qxf1+ 21.Bxf1 Qd5 22.Bd6 1-0

Krogius-Shvedchikov

Calimanesti, 1993

1.d4 d5 2.c4 e6 3.Nc3 Nf6 4.Nf3 c6 5.e3 Nbd7 6.Bd3 dxc4 7.Bxc4 b5 8.Be2 a6 9.e4 b4 10.e5 bxc3 11.exf6 cxb2 12.fxg7 bxa1=Q 13.gxh8=Q Qa5+ 14.Nd2 Bb7 15.O-O Q1xa2 16.Nc4 Qd5 17.Bh6 O-O-O 18.Bxf8 c5 19.Nd6+ Qxd6 20.Bxd6 Rxh8 21.dxc5 Qd5 22.Qxd5 exd5 23.Rc1 1-0

De Guzman (2407)-Bhat (2410)

Michael Franett Memorial

San Francisco, 2005

1.d4 d5 2.c4 e6 3.Nf3 c6 4.e3 Nf6 5.Nc3 Nbd7 6.Bd3 dxc4 7.Bxc4 b5 8.Be2 Bb7 9.e4 b4 10.e5 bxc3 11.exf6 cxb2 12.fxg7 bxa1=Q 13.gxh8=Q Qa5+ 14.Nd2 Qf5 15.O-O O-O-O 16.Qb3 Nc5 17.Qb4 Nd7 18.Qb3 Nc5 19.Qb4 Be7 20.Qg7 Bf8 21.Qh8 Be7 1/2-1/2

Emil Klemanic (2257)-Peter Palecek (2254)

Slovakia Team Ch.

Košice, Jan. 16 2011

1.d4 d5 2.Nf3 Nf6 3.c4 c6 4.e3 e6 5.Nc3 Nbd7 6.Bd3 dxc4 7.Bxc4 b5 8.Be2 a6 9.e4 b4 10.e5 bxc3 11.exf6 cxb2 12.fxg7 bxa1=Q 13.gxh8=Q Qa5+ 14.Nd2 c5 15.O-O Qxd4 16.Qxh7 Qxa2 17.Bc4 Nf6 18.Qh8 Qa5 19.Qf3 Nd5 20.Qhh5 Qc7 21.Re1 Nf4 22.Qh7 Bb7 23.Ne4 Qa5 24.Rd1 O-O-O 25.Rxd4 Qe1+ 26.Bf1 Rxd4 27.Qxf4 Bxe4 28.Qhxf7 Bd6 29.Q4f6 Bc7 30.Q6xe6+ Kb7 31.Qxa6+ Kb8 32.Qe8+ Rd8 33.Qeb5+ 1-0

If 14.Nd2 Q5xa2?!, then White gets an advantage after the simple 15.O-O.

Shumiakina-Mihai

Timisoara, 1994

1.d4 d5 2.c4 e6 3.Nc3 Nf6 4.Nf3 c6 5.e3 Nbd7 6.Bd3 dxc4 7.Bxc4 b5 8.Be2 a6 9.e4 b4 10.e5 bxc3 11.exf6 cxb2 12.fxg7 bxa1=Q 13.gxh8=Q Qa5+ 14.Nd2 Q5xa2 15.O-O Bb7 16.Bc4 Qa4 17.Nb3 Qc3 18.Bxe6 fxe6 19.Bg5 Nf6 20.Qxf6 1-0

Fernando Peralta (2315)-Carlos Gonzalez

Villa Ballester Open, 1996

1.d4 d5 2.c4 e6 3.Nc3 Nf6 4.Nf3 c6 5.e3 Nbd7 6.Bd3 dxc4 7.Bxc4 b5 8.Be2 a6 9.e4 b4 10.e5 bxc3 11.exf6 cxb2 12.fxg7 bxa1=Q 13.gxh8=Q Qa5+ 14.Nd2 Q5xa2 15.O-O Qa4 16.Ne4 Qb4 17.Bd2 Qaxd4 18.Nf6+ Qxf6 19.Qxf6 Nxf6 20.Bxb4 Bxb4 21.Qa4 1-0

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

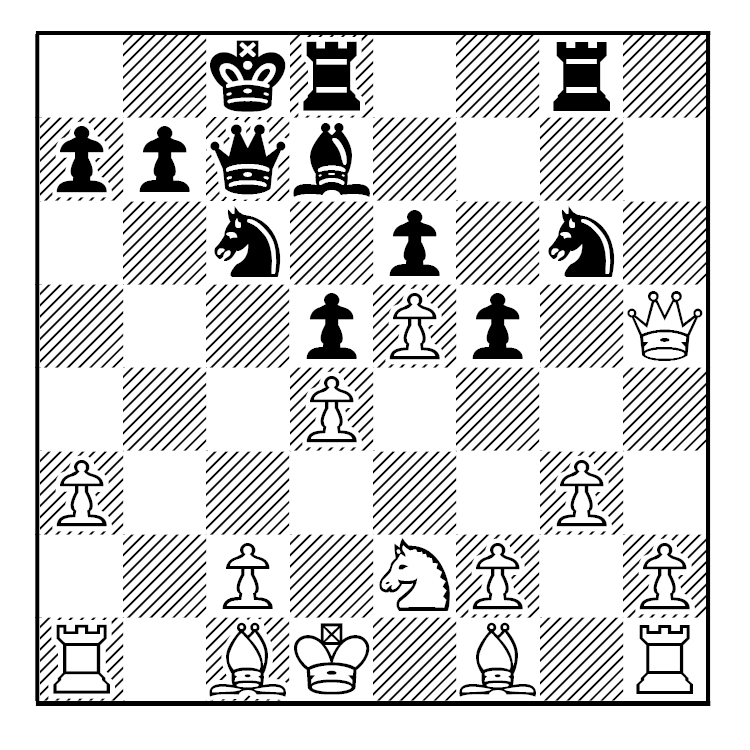

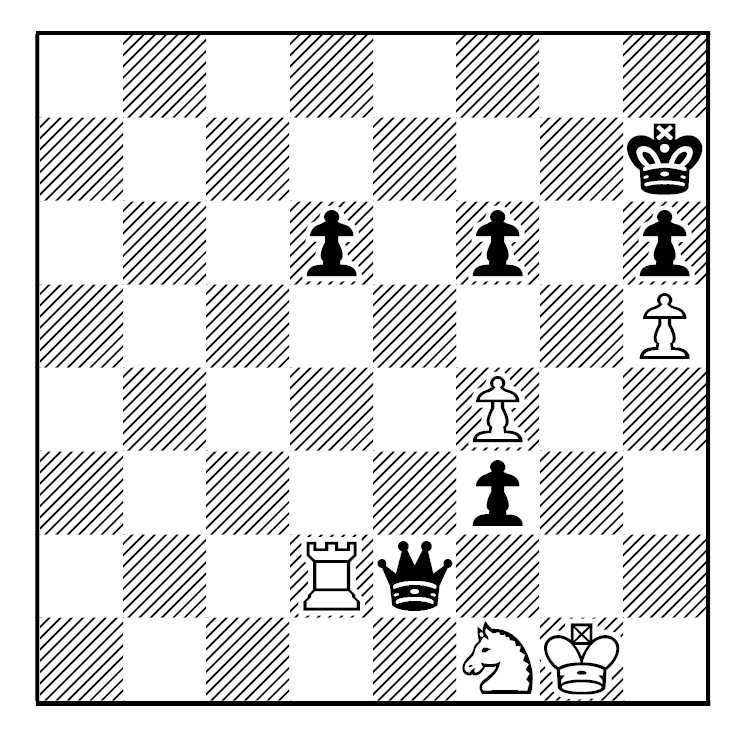

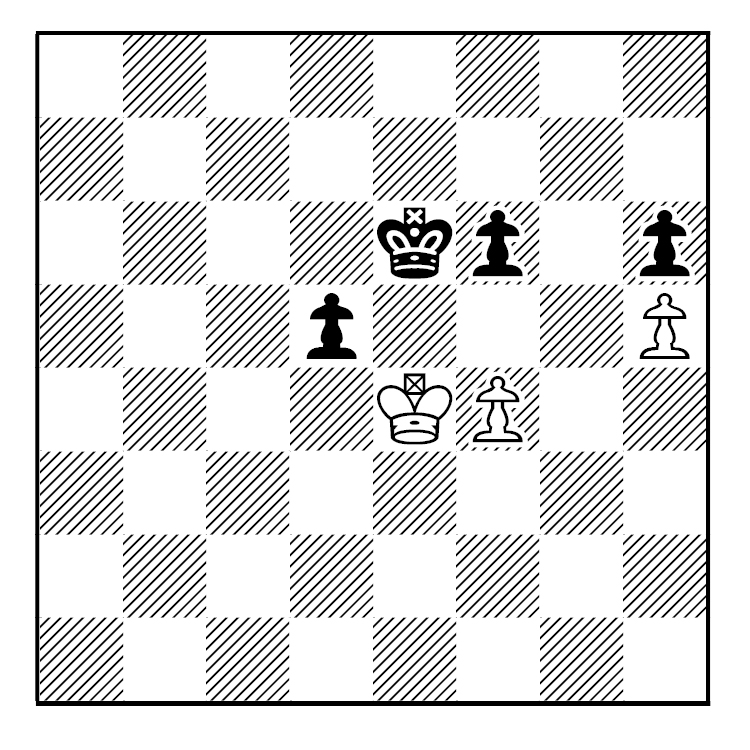

There is a sister variation with 8…Bb7 instead of 8…a6. And although there are similarities between the two variations, Black is more active and scores better in this variation.

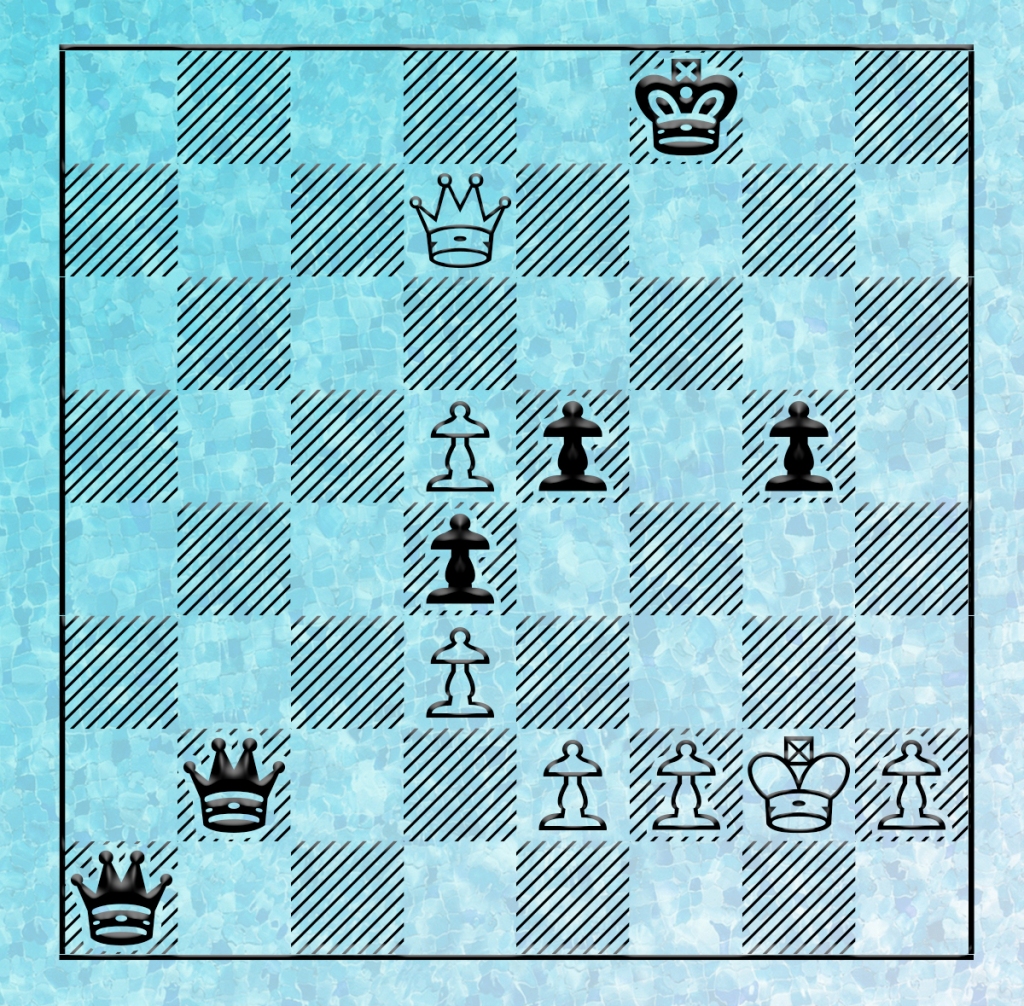

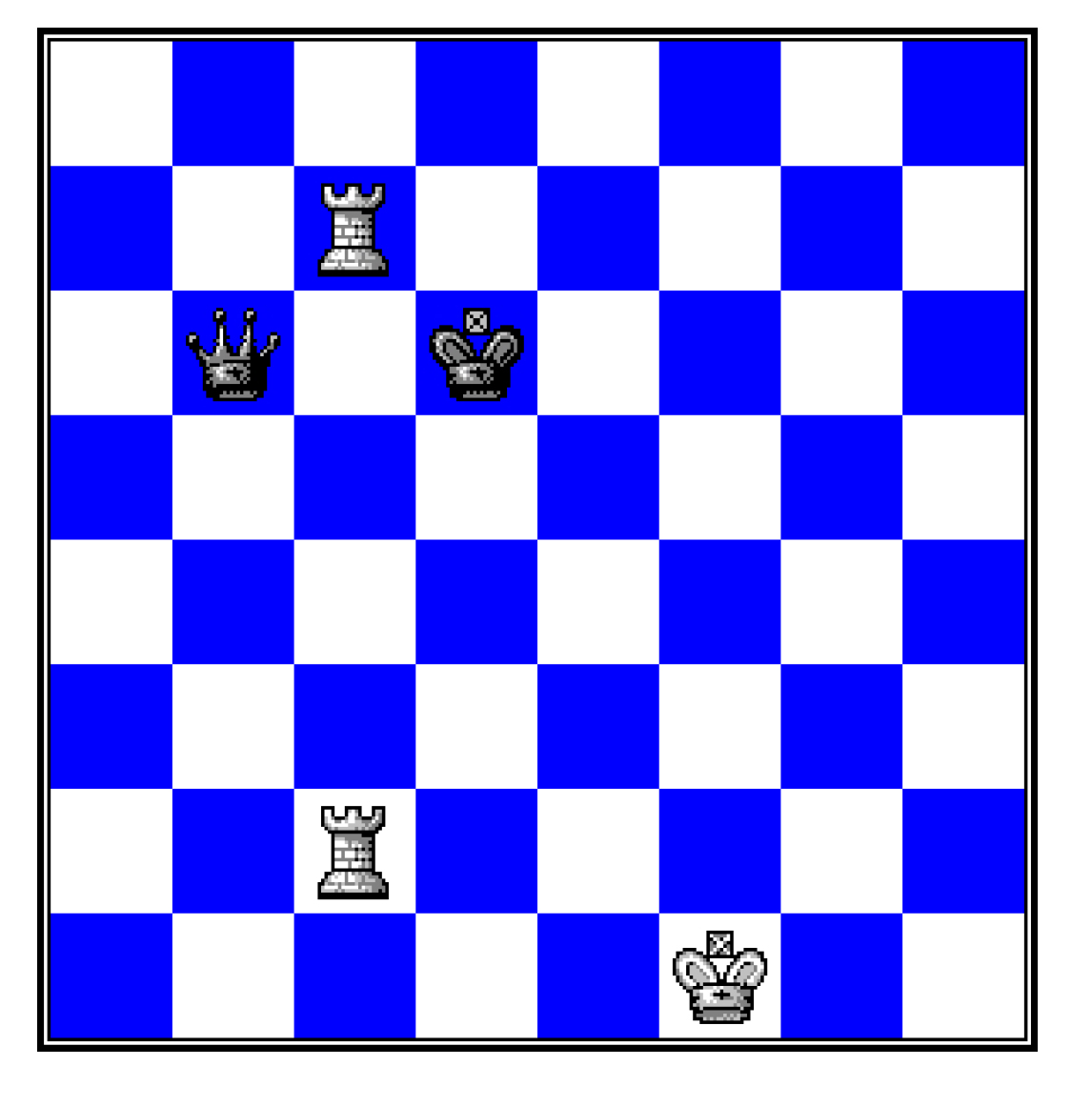

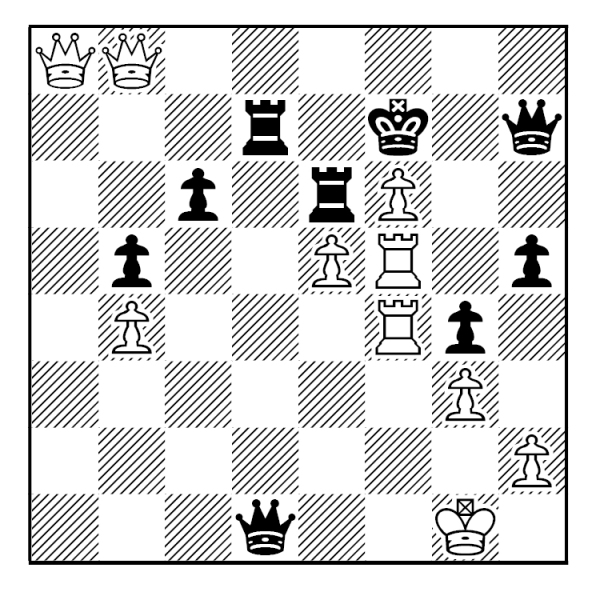

Again, here are the opening moves and a diagram to help.

1.d4 d5 2.c4 e6 3.Nc3 Nf6 4.Nf3 c6 8.Be2 Bb7 9.e4 b4 10.e5! bxc3 11.exf6 cxb2 12.fxg7 bxa1=Q 13.gxh8=Q.

And again, Black does best to activate his second queen with 13…Qa5+. Two games in which he does not and loses the game.

Z. Polgar-V. Dimitrov

Bulgaria, 1984

1.d4 d5 2.c4 e6 3.Nc3 Nf6 4.Nf3 c6 5.e3 Nbd7 6.Bd3 dxc4 7.Bxc4 b5 8.Be2 Bb7 9.e4 b4 10.e5 bxc3 11.exf6 cxb2 12.fxg7 bxa1=Q 13.gxh8=Q Qb1 14.O-O (White’s best.) 14…Qf6 15.Qxf6 Nxf6 16.Ne5 Qxa2 17.Bc4 Qa5 18.Qf3 Be7 19.Bg5 Qd8 20.Bxe6! fxe6 21.Bxf6 +- Qxd4 22.Qh5+ 1-0

Rassmussen-Domosud, 1984

[I am not sure who annotated this game. If the reader knows, please email me with the information. Thanks!]

1.d4 d5 2.c4 e6 3.Nc3 Nf6 4.Nf3 c6 5.e3 Nbd7 6.Bd3 dxc4 7.Bxc4 b5 8.Be2 Bb7 9.e4 b4 10.e5 bxc3 11.exf6 cxb2 12.fxg7 bxa1=Q 13.gxh8=Q Qb1 14.O-O Qf6 15.Qxf6 Nxf6 16.Ne5 Qxa2 17.Bc4 (17.Bh5 Qd5 18.Bxf7+ Kd8 19.Bh5) 17…Qa5 (Qb1) 18.Qf3 Be7 19.Bg5 [19.Nxc6 Qb6 20.d5 exd5 21.Nxe7 dxc4 (21…Kxe7 22.Re1+ Kd7 23.Qf5+ Kd8 24.Bg5)] 19…Qd8 20.Bxe6 [20.Nxc6 Qb6 21.d5 Bxc6 (21…Nxd5 22.Bxd5 <22.Nxe7 Nxe7 23.Qf6 Ng6> 22…Bxg5 23.Ne5) 22.dxc6 Nd5 23.Bxd5 Bxg5] 20…fxe6 21.Bxf6 Qxd4 (21…Qc8 22.Rb1 Bxf6 23.Qxf6 Qc7 24.Qh8+ Ke7 25.Qxh7+ Kd6 26.Nc4+ Kd5 27.Qxc7 Kxc4 28.Qe5 Kc3 29.Qc5+ Kd2 30.Rc1 Kd3 31.Rd1+ Ke4 32.Qe5#) 22.Qh5+ (22…Kd8 23.Nf7+ Kc8 24.Bxd4) 1-0

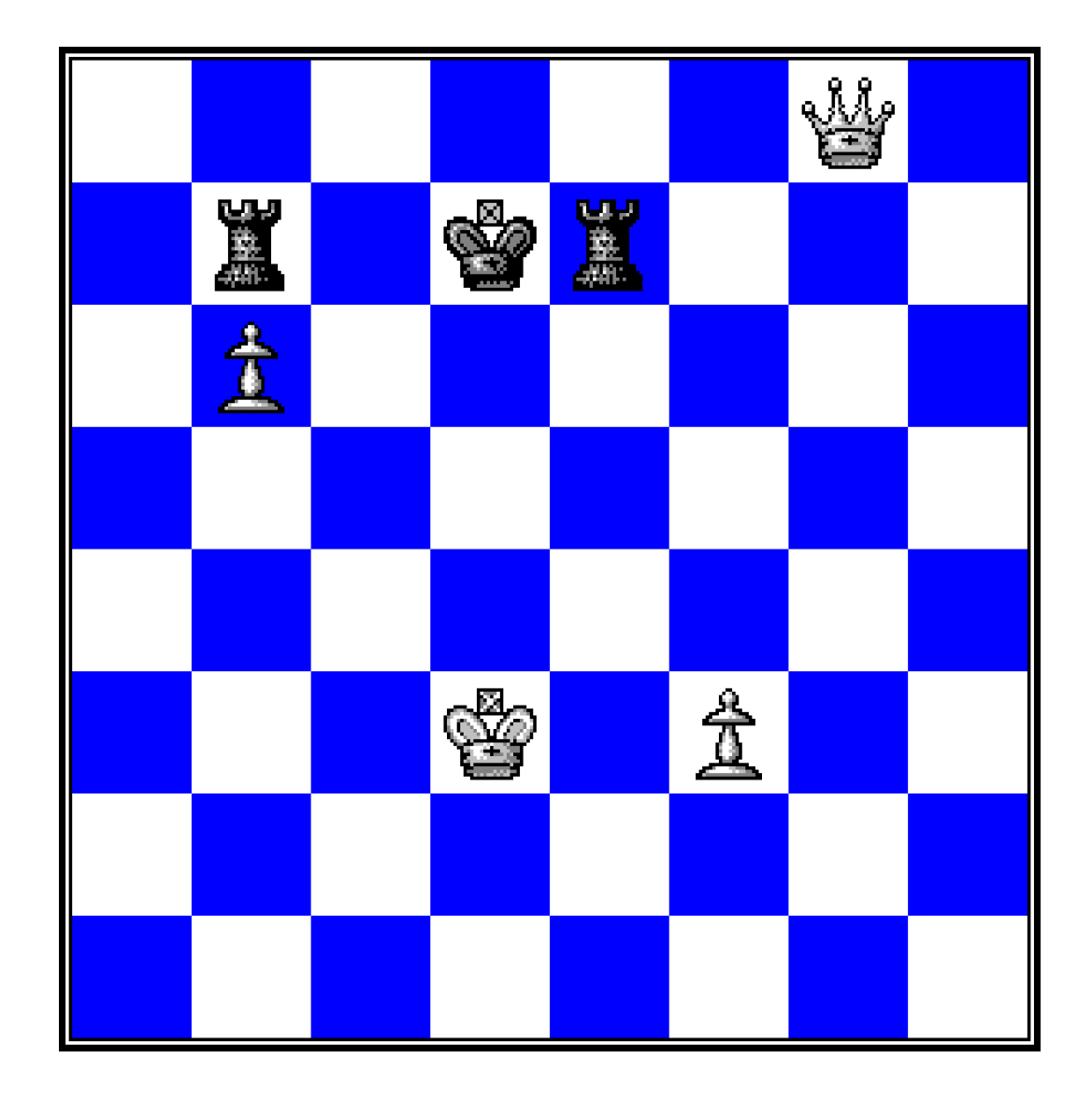

And here is the 14.Bd2 block. Not as good as 14.Nd2, but you probably already knew that already.

Chekover-Suetin

Leningrad, 1951

[ECO]

1.d4 d5 2.c4 e6 3.Nc3 Nf6 4.Nf3 c6 5.e3 Nbd7 6.Bd3 dxc4 7.Bxc4 b5 8.Be2 Bb7 9.e4 b4 10.e5 bxc3 11.exf6 cxb2 12.fxg7 bxa1=Q 13.gxh8=Q Qa5+ 14.Bd2 Qxd1+ 15.Bxd1 Qf5 16.O-O O-O-O 17.Qg8 Be7 18.Qg7 Qg6 19.Qxg6 hxg6=

Pliester-Dreev

New York Open, 1989

1.d4 d5 2.c4 e6 3.Nc3 Nf6 4.Nf3 c6 5.e3 Nbd7 6.Bd3 dxc4 7.Bxc4 b5 8.Be2 Bb7 9.e4 b4 10.e5 bxc3 11.exf6 cxb2 12.fxg7 bxa1=Q 13.gxh8=Q Qa5+ 14.Bd2 Qxd1+ 15.Bxd1 Qf5 16.O-O O-O-O 17.d5 Bd6 18.Qd4 c5 19.Qa4 Qxd5 20.Be2 Rg8 21.Rd1 Qe4 22.Qxe4 Bxe4 23.Ng5 Bd5 24.f3 f5 25.Nxh7 Be7 26.Ba6+ Kc7 27.Bf4+ Kd8 28.h4 Bxh4 29.g3 Bxg3 30.Bg5+ Kc7 31.Kg2 Bf4 0-1

After 13.gxh8=Q Qa5+ 14.Nd2, Black has three reasonable tries. Here are some minor ones just to lay some ground work.

Barshauskas-Kholmov

Latvian Ch., 1955

1.d4 d5 2.c4 e6 3.Nc3 Nf6 4.Nf3 c6 5.e3 Nbd7 6.Bd3 dxc4 7.Bxc4 b5 8.Be2 Bb7 9.e4 b4 10.e5 bxc3 11.exf6 cxb2 12.fxg7 bxa1=Q 13.gxh8=Q Qa5+ 14.Nd2 Q5xa2 15.O-O Ba6 (unclear – ECO) 16.Bxa6 Qxa6 17.Nb3 Qb1 18.Nc5 Qab5 19.Bh6 Qxd1 20.Rxd1 O-O-O 21.Nxd7 Bxh6 22.Qxh7 Qh5 23.Rb1 Kxd7 24.Rb7+ Kc8 25.Qb1 Bf4 26.g3 Rxd4 (with the idea of Rd1+) 0-1

Blackstock-Crouch

London, 1980

1.d4 d5 2.c4 e6 3.Nc3 Nf6 4.Nf3 c6 5.e3 Nbd7 6.Bd3 dxc4 7.Bxc4 b5 8.Be2 Bb7 9.e4 b4 10.e5 bxc3 11.exf6 cxb2 12.fxg7 bxa1=Q 13.gxh8=Q Qa5+ 14.Nd2 Qd5 15.O-O Qaxd4 16.Qxh7 Nf6 17.Qb1 Qb6 18.Bb2 Be7 19.Nc4 Qc7 20.Be5 Qcd7 21.Bxf6 Bxf6 22.Bf3 Qd4 23.Qa4 (+- ECO ; 23…Qf4!?)

Hansen-Muir

Aarus, 1990

1.d4 d5 2.c4 e6 3.Nc3 Nf6 4.Nf3 c6 5.e3 Nbd7 6.Bd3 dxc4 7.Bxc4 b5 8.Be2 Bb7 9.e4 b4 10.e5 bxc3 11.exf6 cxb2 12.fxg7 bxa1=Q 13.gxh8=Q Qa5+ 14.Nd2 Ba6 15.O-O Bxe2 16.Qxe2 Q5xa2 17.Qxh7 Qxd4 18.Qeh5 O-O-O 19.Q5xf7 Bc5 20.Qe4 Rf8 21.Qxd4 Bxd4 22.Qh7 Qd5 23.Nf3 Rxf3 24.gxf3 Ne5 25.Qg8+ Kb7 26.Qg7+ Kb6 27.Qg2 Nxf3+ 28.Kh1 a5 29.Be3 c5 30.Rb1+ Kc6 31.Rc1 a4 32.Bxd4 Nxd4 33.Qxd5+ exd5 34.h4 c4 35.h5 Nf5 36.Kg2 Kc5 37.Kf3 d4 38.Kf4 Nd6 39.h6 c3 40.h7 Nf7 41.Ra1 Kc4 0-1

Sadler-Neverov

Hastings, 1991

1.d4 d5 2.c4 e6 3.Nc3 Nf6 4.Nf3 c6 5.e3 Nbd7 6.Bd3 dxc4 7.Bxc4 b5 8.Be2 Bb7 9.e4 b4 10.e5 bxc3 11.exf6 cxb2 12.fxg7 bxa1=Q 13.gxh8=Q Qa5+ 14.Nd2 O-O-O 15.O-O Qf5 16.Qb3 Nc5 17.Qb4 Nd7 18.Qb3 1-0

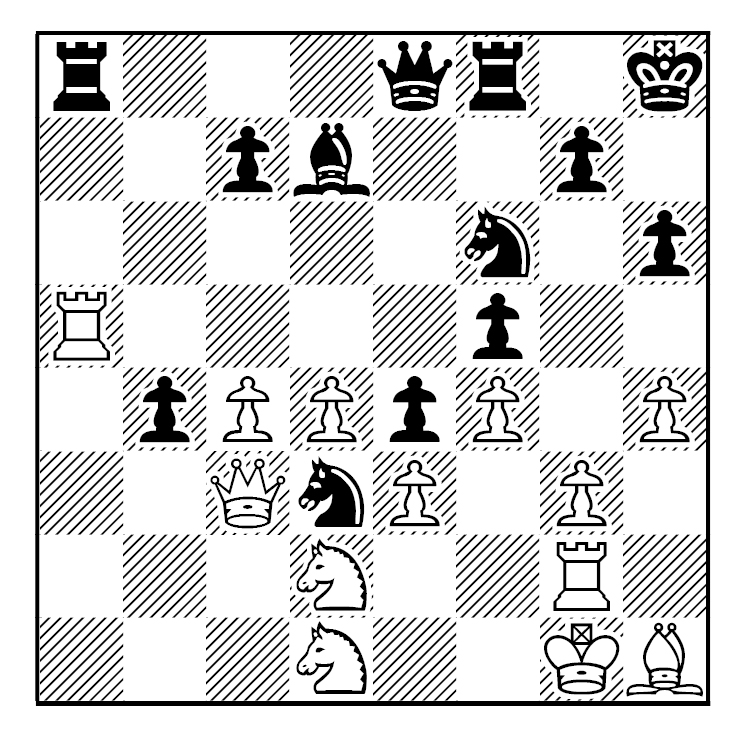

Now for the main lines.

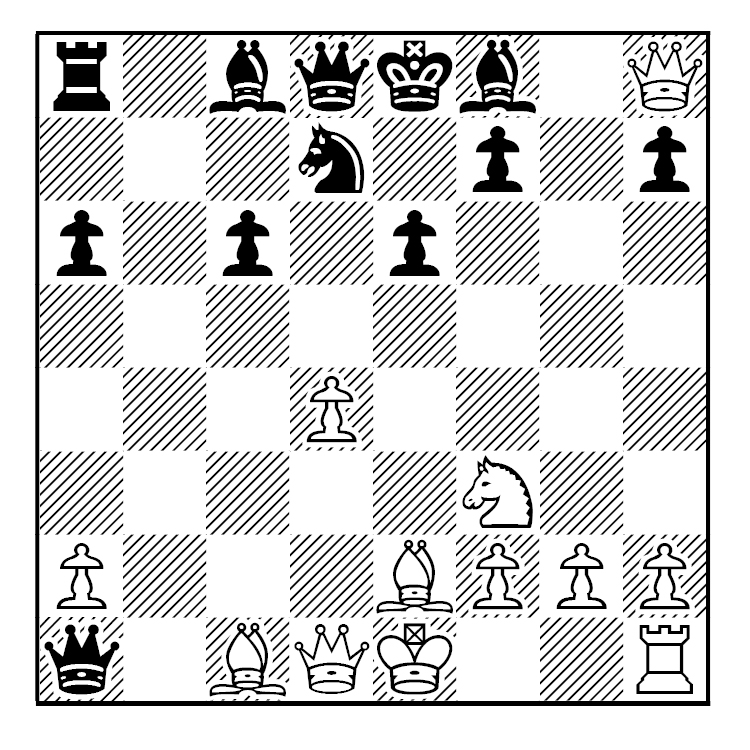

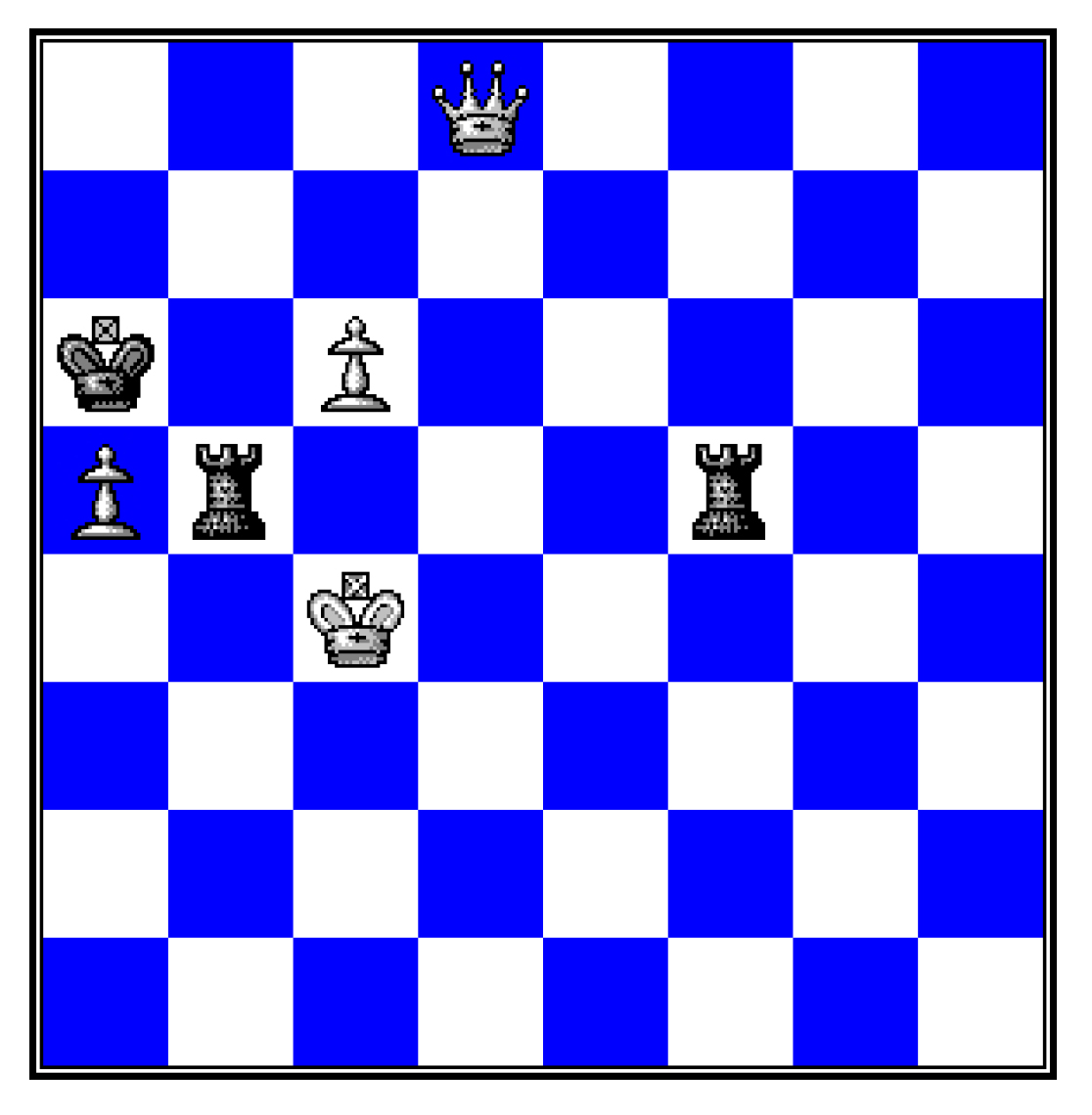

Black’s main choices here;

(1) 13.gxh8=Q Qa5+ 14.Nd2 Q5c3

(2) 13.gxh8=Q Qa5+ 14.Nd2 c5 15.O-O Qxd4

The next two originate from 14.Nd2 Qf5, one with 15.O-O O-O-O 16.Qb3, the other without all these moves.

(3) 13.gxh8=Q Qa5+ 14.Nd2 Qf5

(4) 13.gxh8=Q Qa5+ 14.Nd2 Qf5 15.O-O O-O-O 16.Qb3

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

(1) 13.gxh8=Q Qa5+ 14.Nd2 Q5c3

Lazarev-Goldstein

USSR Ch., 1962

1.d4 d5 2.c4 e6 3.Nc3 Nf6 4.Nf3 c6 5.e3 Nbd7 6.Bd3 dxc4 7.Bxc4 b5 8.Be2 Bb7 9.e4 b4 10.e5 bxc3 11.exf6 cxb2 12.fxg7 bxa1=Q 13.gxh8=Q Qa5+ 14.Nd2 Q5c3 15.O-O Qxd4 16.Qxh7 Qxa2 17.Bc4 Qa5 18.Bxe6 O-O-O 19.Qxf7 Qg7 20.Qxg7 Bxg7 21.Nc4 Qc7 22.Qg4 Be5 23.Bxd7+ Rxd7 24.Qg8+ Rd8 25.Qe6+ 1-0

Bikov-Filipenko

Moscow, 1983

1.d4 d5 2.c4 e6 3.Nc3 Nf6 4.Nf3 c6 5.e3 Nbd7 6.Bd3 dxc4 7.Bxc4 b5 8.Be2 Bb7 9.e4 b4 10.e5 bxc3 11.exf6 cxb2 12.fxg7 bxa1=Q 13.gxh8=Q Qa5+ 14.Nd2 Q5c3 15.Bc2 Ba6 16.h4 Qxd4 17.Qxd4 Qxd4 18.Rh3 O-O-O 19.Qf3 Ne5 20.Qc3 Bb4 21.Qxd4 Rxd4 22.h5 Nd3+ 23.Bxd3 Bxd3 24.h6 c5 25.a3 Ba5 26.Rh5 Rd5 27.Rxd5 exd5 28.Kd1 Bg6 29.Nb3 Bb6 30.a4 c4 31.a5 Bxf2 32.Ke2 Bg1 33.Kf1 Bh2 34.Nd4 Kd7 35.Bb2 Bf4 36.Bc3 a6 37.Ke2 Bxh6 0-1

(2) 13.gxh8=Q Qa5+ 14.Nd2 c5 15.O-O Qxd4

Lukov-Conquest

Tbilisi, 1988

1.d4 d5 2.c4 e6 3.Nc3 Nf6 4.Nf3 c6 5.e3 Nbd7 6.Bd3 dxc4 7.Bxc4 b5 8.Be2 Bb7 9.e4 b4 10.e5 bxc3 11.exf6 cxb2 12.fxg7 bxa1=Q 13.gxh8=Q Qa5+14.Nd2 c5 15.O-O Qxd4 16.Qxh7 Qc7 17.Bf3 Nf6 18.Qh3 Nd5 19.Ne4 Qxd1 20.Rxd1 O-O-O 21.Bg5 Be7 22.Bxe7 Qxe7 23.Qh6 Kb8 24.Rc1 Rc8 25.Qg7 e5 26.Bg4 f5 27.Qxe7 Nxe7 28.Nd6 fxg4 29.Nxc8 Bxc8 30.Rxc5 Ng6 31.f3 gxf3 32.gxf3 Be6 33.a3 Kb7 34.Kf2 Kb6 35.Rc3 Bf5 36.Kg3 e4 37.Re3 exf3 38.Rxf3 Ne7 39.Kf4 Bc8 40.Kg5 Kc5 41.h4 Bb7 42.Rf7 Kd6 43.Kf6 Nd5+ 44.Kg7 Nc7 45.h5 Be4 46.h6 a5 47.Rf1 Ke5 48.Rc1 Ne6+ 49.Kg8 Kd4 50.Rg1 Nc5 51.Kf7 Bc2 52.Kf6 Nd7+ 53.Kg7 Nc5 54.Kf7 Bh7 55.Ke7 Bf5 56.Rg5 Bc2 57.Rh5 Bh7 58.Kd6 Nb3 59.Kc6 Kc3 60.Kb5 Bd3+ 61.Ka4 1-0

Sadler-Payen

Hastings, 1990

1.d4 d5 2.c4 e6 3.Nc3 Nf6 4.Nf3 c6 5.e3 Nbd7 6.Bd3 dxc4 7.Bxc4 b5 8.Be2 Bb7 9.e4 b4 10.e5 bxc3 11.exf6 cxb2 12.fxg7 bxa1=Q 13.gxh8=Q Qa5+14.Nd2 c5 15.O-O Qxd4 16.Qxh7 Qxa2 17.Bc4 Qaa1 18.Bxe6 O-O-O 19.Qxf7 Bd6 20.Nc4 Bc7 21.Bd5 Ba6 22.Qxd4 Qxd4 23.Bb2 Qd3 24.Qe6 Bb5 25.Re1 Kb8 26.Ne3 Qd2 27.Rb1 Nb6 28.Be5 Qd3 29.Be4 Qe2 30.Bxc7+ Kxc7 31.Qe5+ Kc8 1-0

Chatalbashev-Sveshnikov

USSR, 1991

1.d4 d5 2.c4 e6 3.Nc3 Nf6 4.Nf3 c6 5.e3 Nbd7 6.Bd3 dxc4 7.Bxc4 b5 8.Be2 Bb7 9.e4 b4 10.e5 bxc3 11.exf6 cxb2 12.fxg7 bxa1=Q 13.gxh8=Q Qa5+14.Nd2 c5 15.O-O Qxd4 16.Nb3 Qxh8 (16…Qxd1 17.Rxd1 Qa4 18.Qxh7) 17.Nxa5 Bd5 18.Qc2 (18.Bf3!? Qd4 19.Qxd4 cxd4 20.Bxd5 exd5 21.Re1+ Kd8 22.Nc6+) 18…Qe5 19.Bd3 Bg7 20.Nc4 Qc3 21.Qe2 Ne5 22.Nxe5 Qxe5 23.Be3 Rc8 24.Ba6 Rc7 25.Qb5+ Ke7 26.Bxc5+ Kf6 27.Qb4 Qg5 28.f3 Kg6 29.Bd3+ f5 30.a3 Be5 31.Bd4 a5 32.Qb6 Rb7 33.Qc5 Qe7 34.Bf2 Qxc5 35.Bxc5 Rc7 36.Rc1 Rxc5 0-1

(3) 13.gxh8=Q Qa5+ 14.Nd2 Qf5

Pliester-Nikolic

Purmerend, 1993

1.d4 d5 2.c4 e6 3.Nc3 Nf6 4.Nf3 c6 5.e3 Nbd7 6.Bd3 dxc4 7.Bxc4 b5 8.Be2 Bb7 9.e4 b4 10.e5 bxc3 11.exf6 cxb2 12.fxg7 bxa1=Q 13.gxh8=Q Qa5+ 14.Nd2 Qf5 15.Nc4 O-O-O 16.O-O Qxa2 17.Bd3 Qd5 18.Ne3 Qg5 19.Qxh7 Qg7 20.Qdh5 Qxh7 21.Qxh7 e5 22.Bc4 Qa5 23.Qxf7 exd4 24.Nf5 Bc5 25.Bg5 Rf8 26.Qe6 Qc7 27.g3 Qe5 28.Qxe5 Nxe5 29.Be6+ Nd7 30.Rb1 Ba6 31.Rc1 Re8 32.Ng7 Rxe6 33.Nxe6 Bb6 34.h4 Kb7 35.h5 c5 36.Be7 d3 37.h6 c4 38.h7 d2 39.Ra1 c3 40.h8=Q c2 41.Qh1+ Kc8 42.Qc6+ 1-0

Carnic-Vlatkovic, 1995

1.d4 d5 2.c4 e6 3.Nc3 Nf6 4.Nf3 c6 5.e3 Nbd7 6.Bd3 dxc4 7.Bxc4 b5 8.Be2 Bb7 9.e4 b4 10.e5 bxc3 11.exf6 cxb2 12.fxg7 bxa1=Q 13.gxh8=Q Qa5+ 14.Nd2 Qf5 15.O-O O-O-O 16.Nc4 Be7 17.Qg7 Qxa2 18.Bd3 Qf6 19.Qg3 Nb6 20.Nxb6+ axb6 21.Be3 Qd5 22.Qc2 Bd6 23.Qh3 c5 24.f3 Bf4 25.Bf2 Qd6 26.Rd1 Kb8 27.dxc5 bxc5 28.Bxc5 Qc7 29.Qh5 Rd5 30.Qxd5 exd5 31.g3 0-1

Shumiakina-Zakurdjaeva

Moscow, 1999

1.d4 d5 2.c4 e6 3.Nc3 Nf6 4.Nf3 c6 5.e3 Nbd7 6.Bd3 dxc4 7.Bxc4 b5 8.Be2 Bb7 9.e4 b4 10.e5 bxc3 11.exf6 cxb2 12.fxg7 bxa1=Q 13.gxh8=Q Qa5+ 14.Nd2 Qf5 15.O-O O-O-O 16.Nc4 Qxa2 17.Bd3 Qf6 18.Qxh7 Nb6 19.Nxb6+ axb6 20.Be3 Bd6 21.Qdh5 Rd7 22.Be4 Qd8 23.Q7h6 Qa4 24.Bf3 Kc7 25.Qh8 Qxh8 26.Qxh8 Qa5 27.Qf6 Qa8 28.Rb1 b5 29.Rc1 Qd8 30.Qh6 Qf8 31.Qh5 f5 32.Bd2 b4 33.Qg6 Qh8 34.g3 Qxd4 35.Be3 Qe5 36.Rd1 Rg7 37.Qh6 Rd7 38.Bd4 Qb5 39.Qxe6 f4 40.Be2 Qg5 41.Bb6+ Kxb6 42.Qxd7 Bc7 43.Bf3 fxg3 44.hxg3 Qc5 45.Kg2 Qc3 46.Rh1 b3 47.Rh7 Qe5 48.Re7 Qd6 49.Qxd6 Bxd6 50.Re3 Kb5 51.Rxb3+ Bb4 52.Rb1 Kc4 53.Be4 1-0

(4) 13.gxh8=Q Qa5+ 14.Nd2 Qf5 15.O-O O-O-O 16.Qb3

Koziak-Vidoniak

Russia, 1991

1.d4 d5 2.c4 e6 3.Nc3 Nf6 4.Nf3 c6 5.e3 Nbd7 6.Bd3 dxc4 7.Bxc4 b5 8.Be2 Bb7 9.e4 b4 10.e5 bxc3 11.exf6 cxb2 12.fxg7 bxa1=Q 13.gxh8=Q Qa5+ 14.Nd2 Qf5 15.O-O O-O-O 16.Qb3 Bd6 17.Nc4 Be7 18.Qg7 Nc5 19.Qb4 Bh4 20.Be3 Qxa2 21.dxc5 Qxe2 22.Nd6+ Rxd6 23.cxd6 Qxf1+ 24.Kxf1 Qd3+ 25.Ke1 Qxe3+ 26.Kd1 Qd3+ 27.Kc1 Qf1+ 28.Kb2 Qxf2+ 29.Ka3 Qe3+ 30.Ka4 Qd3 31.Qxh4 Qd1+ 32.Ka3 Qd3+ 33.Ka2 Qa6+ 34.Kb3 1-0

Sadler-Kaidanov

Andorra, 1991

1.d4 d5 2.c4 e6 3.Nc3 Nf6 4.Nf3 c6 5.e3 Nbd7 6.Bd3 dxc4 7.Bxc4 b5 8.Be2 Bb7 9.e4 b4 10.e5 bxc3 11.exf6 cxb2 12.fxg7 bxa1=Q 13.gxh8=Q Qa5+ 14.Nd2 Qf5 15.O-O O-O-O 16.Qb3 Nc5 17.Qb4 Qc2 18.Qf6 Qcc3 19.Qxc3 Qxc3 20.Nf3 Ne4 21.Qxf7 c5 22.Bf4 Bd6 23.Qxe6+ Kb8 24.Bxd6+ Nxd6 25.Qe7 Qa5 26.dxc5 Nc8 27.Qe5+ Qc7 28.Qxc7+ Kxc7 29.Rd1 Re8 30.Bb5 Rg8 31.Rd7+ Kb8 32.c6 Ba8 33.Ne5 a5 34.Rxh7 1-0

Gil Capape-San Segundo

Saragossa, 1992

1.d4 d5 2.c4 e6 3.Nc3 Nf6 4.Nf3 c6 5.e3 Nbd7 6.Bd3 dxc4 7.Bxc4 b5 8.Be2 Bb7 9.e4 b4 10.e5 bxc3 11.exf6 cxb2 12.fxg7 bxa1=Q 13.gxh8=Q Qa5+ 14.Nd2 Qf5 15.O-O O-O-O 16.Qb3 Nc5 17.Qa3 Qxd4 18.Qxd4 Rxd4 19.Nc4 Qc2 20.Qf3 Nd7 21.Be3 c5 22.Qxf7 Qxe2 23.Bxd4 Qe4 24.Qxf8+ 1-0

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

And now you, the extremely tactically inclined player, can analyze these preceding games, and perhaps even use the ideas you can find, for your future games.