Perhaps the most popular games ever published are those in which a player sacrifices his one and only Queen. Bravery is required for that player who thrusts his most valuable piece into the fight, sometimes with no hope of ever seeing her alive again.

In the over 500 years of chess, fewer topics have been more exciting, more spectacular, and more aesthetically pleasing to the player than when he freely sacrifices his powerful Queen. In all cases, the desired result, whether immediately or indirectly, is to gain something more valuable; the enemy King.

Basically, there are three types of tactical Queen sacrifices. The first type is the one made for material gain. Sometimes called a pseudo-sacrifice, the Queen is given up and won back a few moves later.

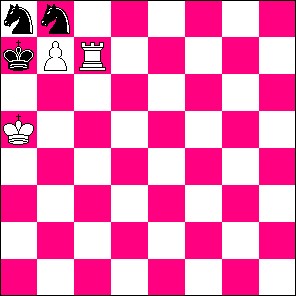

Doroshkevich-Astashin

USSR, 1967 (D24)

1.d4 d5 2.c4 dxc4 3.Nf3 Nf6 4.Nc3 a6 5.e4 b5 6.e5 Nd5 7.a4 Nxc3 8.bxc3 Bb7 9.e6 fxe6 10. Be2 Qd5 11.Ng5 Qxg2 12.Rf1 Bd5 13.axb5 Qxh2?! 14.Bg4 h5 15.Bxe6 Bxe6 16.Qf3 c6 17.Nxe6 Qd6 18.Qf5 g6 19.Qxg6+ Kd7 20.Nc5+ Kc8 21.Qe8+ Qd8 22.b6! 1-0

The Queen pseudo-sacrifice sacrifice for gain may turn into a mate if the opponent tries to hold on the extra female material.

Muller-Calderone

Compuserve, 1996 (B57)

1.e4 c5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 cxd4 4.Nxd4 Nf6 5.Nc3 Nc6 6.Nxc6 bxc6 7.Bc4 g6 8.e5 Nd7 (Certainly not 8…dxe5?? 9.Bxf7+. Best is 8…Ng4) 9.exd6 exd6 10.O-O Nf6 11.Re1+ Be7 12.Qf3 O-O 13.Qxc6 Bf5 14.Bh6 Re8 15.Nd5 Rc8

16.Qxe8+! Qxe8 17.Nxe7+ Kh8 18.Nxf5 Ne4 19.Nxd6 Qc6 20.Nxf7+ (20…Kg8 21.Ne5+) 1-0

Levitzky-Marshall

Breslau 1912 (C10)

[Chernev says that spectators showered the board with gold pieces after Black’s 23rd move. Soltis says it was bettors who lost the wager on the outcome.]

1.d4 e6 2.e4 d5 3.Nc3 c5 (The Marshall Gambit, as played by its inventor.) 4.Nf3 Nc6 5.exd5 exd5 6.Be2 Nf6 7.O-O Be7 8.Bg5 O-O 9.dxc5 Be6 10.Nd4 Bxc5 11.Nxe6 fxe6 12.Bg4 Qd6 13.Bh3 Rae8 14.Qd2 Bb4 15.Bxf6 Rxf6 16.Rad1 Qc5 17.Qe2 Bxc3 18.bxc3 Qxc3 19.Rxd5 Nd4 20.Qh5 Ref8 21.Re5 Rh6 22.Qg5 Rxh3 23.Rc5 Qg3!!

[O.K. Here are the variations: 24.Qxg3 Ne2+ 25.Kh1 Nxg3+ 26.Kg1 Nxf1 27.gxh3 Nd2 and extra piece wins. If White tries to hold onto the Queen, he tries loses his King. 24.hxg3 Ne2#, or 24.fxg3 Ne2+ 25.Kh1 Rxf1#.] 0-1

A second popular Queen sacrifice is made solely for to checkmate an opponent. The mate may be immediate as these short games show.

De Legal-Saint Brie

Paris, 1750? (C40)

1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 d6 3.Bc4 (3.d4 is now considered to be the best move when facing Philidor’s Defence. But then we would miss all the fun of this classical trap!) 3…Bg4? 4.Nc3 g6 5.Nxe5! Bxd1 6.Bxf7+ Ke7 7.Nd5mate 1-0

Greco-N.N.,

Rome, 1620?

(B20)

1.e4 b6 2.d4 Bb7 3.Bd3 f5 4.exf5 Bxg2 5.Qh5+ g6 6.fxg6 Nf6? (If Black plays 6..e5?, then White has the beautiful 7.g7+ Ke7 8.Qxe5+ Kf7 9.gxh8=N#!) 7.gxh7+! Nxh5 8.Bg6mate 1-0

Paul Morphy-Duke of Brunswick and Count Isouard

Paris, 1858 (C41)

[A short classic that displays all the qualities that make up a great game; rapid development, pins, sacrifices, and slightly inferior moves by the opponent.]

1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 Bg4? 4.dxe5 (Simple enough. White threatens 4…dxe5 5.Qxd8+ Kxd8 6.Nxe5, netting a pawn.) 4…Bxf3 5.Qxf3 dxe5 6.Bc4 Nf6 7.Qb3 Qe7 8.Nc3 c6 9.Bg5 b5 10.Nxb5! (The whole mating sequence begins with a Knight sacrifice.) 10…cxb5 11.Bxb5+ Nbd7 12.O-O-O! Rd8 13.Rxd7 Rxd7 14.Rd1 Qe6 15.Bxd7+ Nxd7 16.Qb8+! (And ends with a Queen deflection sacrifice!) 16…Nxb8 17.Rd8mate 1-0

Queen sacrifices for the checkmate may also be slightly more involved and take longer to execute the mate.

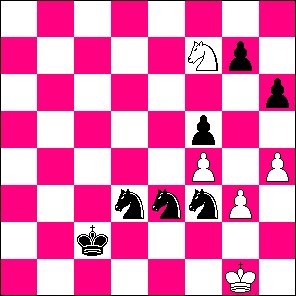

Maryasin-Kapengut

Minsk, 1969 (D01)

1.d4 Nf6 2.Nc3 d5 3.Bg5 (The often neglected Veresov’s Opening.) 3…Nbd7 4.Nf3 g6 5.e3 Bg7 6.Bd3 c5 7.Ne5 O-O 8.Qf3 Qb6 9.O-O-O e6 10.h4 Nxe5 11.dxe5 Nd7 12.h5 Nxe5 13.Qh3 f5 14.hxg6 hxg6 15.Be2 d4 16.Na4 Qb4 17.f4 Qxa4 18.fxe5 Qxa2 19.Qh7+ Kf7 20.Bf6 Qa1+ 21.Kd2 Qa5+ 22.c3 Rg8

23.Qxg6+! Kxg6 24.Bh5+ Kh7 25.Bf7+ Bh6 26.Rxh6+ (with the idea of Rh1#) 1-0

The third type of Queen sacrifices are those initiating King hunts. The Queen is given up so that the enemy King is brought out into the open. The checkmate, if there, comes many moves later.

These sacrifices differ from the mating sacrifices in that, while a mating sacrifice can be usually calculated out to the end, a King Hunt is made on a player’s belief that he can find a mate somewhere down the line. In other words, a King Hunt is made more on intuition rather than calculation.

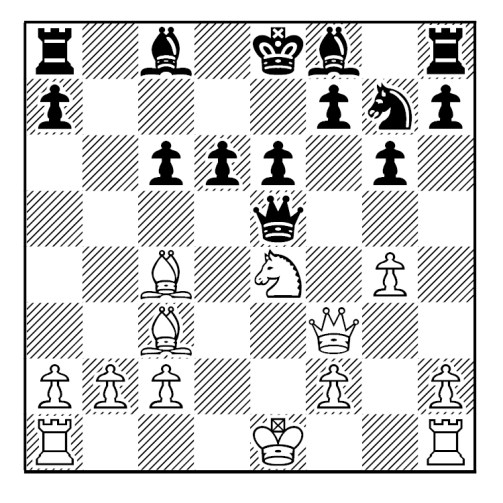

D. Byrne-Fischer

Rosenwald Memorial

New York 1956 (D97)

1.Nf3 Nf6 2.c4 g6 3.Nc3 Bg7 4.d4 O-O 5.Bf4 d5 6.Qb3 dxc4 7.Qxc4 c6 8.e4 Nbd7 9.Rd1 Nb6 10.Qc5 Bg4 11.Bg5 Na4 12.Qa3 Nxc3 13.bxc3 Nxe4 14.Bxe7 Qb6 15.Bc4 Nxc3 16.Bc5 Rfe8+ 17.Kf1 Be6!!

18.Bxb6 Bxc4+ 19.Kg1 Ne2+ 20.Kf1 Nxd4+ 21.Kg1 Ne2+ 22.Kf1 Nc3+ 23.Kg1 axb6 24.Qb4 Ra4 25.Qxb6 Nxd1 26.h3 Rxa2 27.Kh2 Nxf2 28.Re1 Rxe1 29.Qd8+ Bf8 30.Nxe1 Bd5 31.Nf3 Ne4 32.Qb8 b5 33.h4 h5 34.Ne5 Kg7 35.Kg1 Bc5+ 36.Kf1 Ng3+ 37.Ke1 Bb4+ 38.Kd1 Bb3+ 39.Kc1 Ne2+ 40.Kb1 Nc3+ 41.Kc1 Rc2mate 0-1

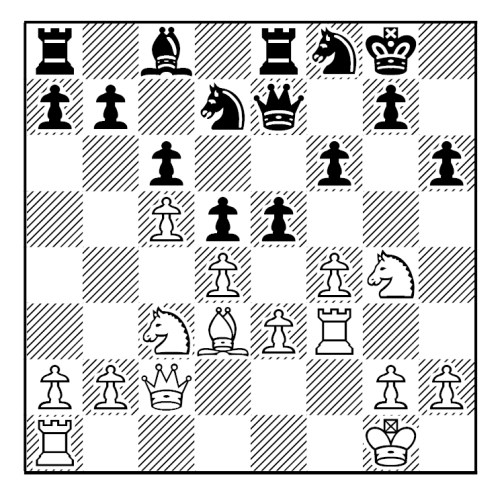

Averbakh-Kotov

Zurich, 1953 (A55)

1.d4 Nf6 2.c4 d6 3.Nf3 Nbd7 4.Nc3 e5 5.e4 Be7 6.Be2 O-O 7.O-O c6 8.Qc2 Re8 9.Rd1 Bf8 10.Rb1 a5 11.d5 Nc5 12.Be3 Qc7 13.h3 Bd7 14.Rbc1 g6 15.Nd2 Rab8 16.Nb3 Nxb3 17.Qxb3 c5 18.Kh2 Kh8 19.Qc2 Ng8 20.Bg4 Nh6 21.Bxd7 Qxd7 22.Qd2 Ng8 23.g4 f5 24.f3 Be7 25.Rg1 Rf8 26.Rcf1 Rf7 27.gxf5 gxf5 28.Rg2 f4 29.Bf2 Rf6 30.Ne2

30…Qxh3+!! 31.Kxh3 Rh6+ 32.Kg4 Nf6+ 33.Kf5 Nd7 34.Rg5 Rf8+ 35.Kg4 Nf6+ 36.Kf5 Ng8+ 37.Kg4 Nf6+ 38.Kf5 Nxd5+ 39.Kg4 Nf6+ 40.Kf5 Ng8+ 41.Kg4 Nf6+ 42.Kf5 Ng8+ (These last few moves were apparently played to reach adjournment.) 43.Kg4 Bxg5 44.Kxg5 Rf7 45.Bh4 Rg6+ 46.Kh5 Rfg7 47.Bg5 Rxg5+ 48.Kh4 Nf6 49.Ng3 Rxg3 50.Qxd6 R3g6 51.Qb8+ Rg8 0-1

Mating threats may occur more than once in a game. Which also means a player can sometimes a player can offer his original Queen more than once.

Nigmadzianov-Kaplun

USSR 1977 (B05)

1.e4 Nf6 2.e5 Nd5 3.d4 d6 4.Nf3 Bg4 5.Be2 c6 6.c4 Nb6 7.Nbd2 N8d7? (ECO suggests 7…dxe5.) 8.Ng5! Bxe2 9.e6!! (White offers his Queen for the first time. This offer can be turned down.) 9…f6 (9…Bxd1? fails to 10.exf7#) 10.Qxe2 fxg5 11.Ne4 +/- Nf6 12.Nxg5 Qc7 13.Nf7 Rg8 14.g4 h6 15.h4 d5 16.c5 Nc8 17.g5 Ne4 18.gxh6 gxh6 19.Qh5 Nf6 20.Nd6+ Kd8 21.Qe8+ (The second offer cannot be refused.) 1-0

Gonssiorovsky-Alekhine

Odessa 1918 (C24)

1.e4 e5 2.Bc4 Nf6 3.d3 c6 4.Qe2 Be7 5.f4 d5 6.exd5 exf4 7.Bxf4 O-O 8.Nd2 cxd5 9.Bb3 a5 10.c3 a4 11.Bc2 a3 12.b3?! (12.Rb1 is better. Lusin-Morgado, corres.1968 continued with 12…Bd6 13.Qf2 Ng4 14.Qg3 Re8+ 15.Kd1 Ne3+ 16.Kc1 Nf5 17.Qf2 Bxf4 18.Qxf4 Re1+ 19.Bd1 Ne3 20.Ngf3 Rxh1 21.Qxe3 axb2+ 22.Rxb2 Nc6 23.a4 Rxa4 24.Qe2 Ra1+ 25.Rb1 Rxb1+ 26.Nxb1 h6 27.Nbd2 Qe7 28.Kb2 Qxe2 29.Bxe2 g5 30.Nf1 Bg4 31.Ng3 Bxf3 32.Bxf3 Rxh2 33.Bxd5 h5 34.Kc1 Kg7 35.Kd2 Ne5 36.d4 Ng4 37.Ke2 h4 38.Nf1 Rh1 39.Bxb7 h3 40.gxh3 Rxh3 41.c4 f5 42.c5 Kf6 43.c6 Rc3 1/2-1/2) 12…Re8 13.O-O-O Bb4 14.Qf2 Bxc3 15.Bg5 Nc6 16.Ngf3 d4 17.Rhe1 Bb2+ 18.Kb1 Nd5! (The Queen is offered for the first time.)

19.Rxe8+ (Naturally 19.Bxd8 fails to 19…Nc3#) 19…Qxe8 20.Ne4 Qxe4! (The second offer!) 21.Bd2 Qe3 (The third offer!) 22.Re1 (Now White gets into the act!) 22…Bf5 23.Rxe3 dxe3 24.Qf1 exd2 25.Bd1 Ncb4! (And White finally realizes that he cannot stop Nc3#.) 0-1

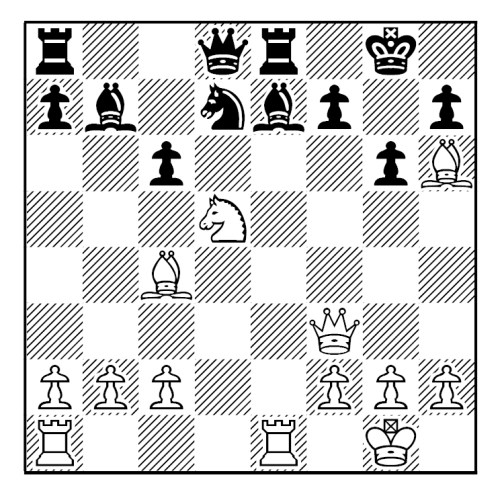

E. Z. Adams-C. Torre

New Orleans 1920 (C62)

1.e4 e5 2.Nf3 d6 3.d4 (Ah!, there is the better move in Philidor’s Defence) 3…exd4 4.Qxd4 Nc6 5.Bb5 Bd7 6.Bxc6 Bxc6 7.Nc3 Nf6 8.O-O Be7 9.Nd5 Bxd5 10.exd5 O-O 11.Bg5 c6 12.c4 cxd5 13.cxd5 Re8 14.Rfe1 a5 15.Re2 Rc8 16.Rae1 Qd7 17.Bxf6 Bxf6

18.Qg4! (The first offer) 18…Qb5 19.Qc4! (The second offer) 19…Qd7 20.Qc7! (The third!) 20…Qb5 21.a4! Qxa4 22.Re4 Qb5 23.Qxb7 (This, the fourth offer, is too much for Black to handle.) 1-0